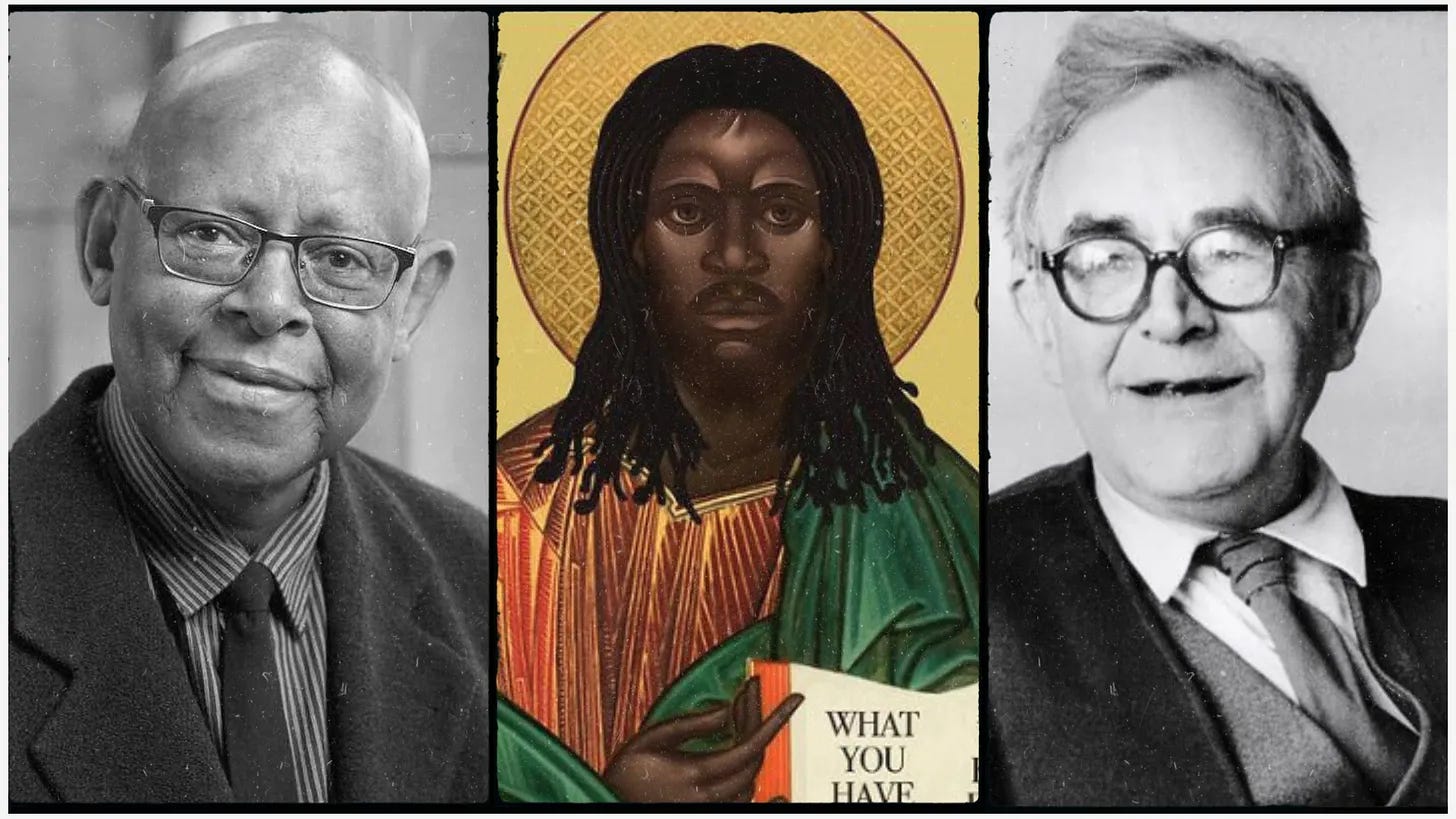

About the author: Chris Boesel is associate professor of Christian theology at Drew Theological School. His primary interest is the extent to which traditional confessions of faith can be seen to call for progressive socio-political visions and commitments. He is the author of In Kierkegaard's Garden with the Poppy Blooms: Why Derrida Does Not Read Kierkegaard when He Reads Kierkegaard (Lexington/Fortress Academic, 2021) and Reading Karl Barth: Theology that Cuts Both Ways (Cascade, 2023).

This post is the seventh in a year-long series putting Barth’s theology in conversation with black theological voices. Our primary question: To what extent is Barth’s theology complicit in the silence of white Barthians on racism in the U.S. and to what extent might Barth’s theology function as an anti-racist resource.

In recent posts, we have been pursuing the question of why, given his similarities with James Cone on Christocentric concreteness, and the indisputable reality of white supremacy in his European context, Barth does not employ the language of divine blackness in a way similar to Cone. I have suggested that certain structural dimensions in Barth’s theology may be seen as preventing him—and U.S. Barthians informed by his work—from following through on the implications of his commitment to Christocentric concreteness in this particular way. I will try to demonstrate this by looking at his mature Christology in the fourth volume of Church Dogmatics over the next few posts. In this post we will look at part one of volume four, focusing on the central theme: “The Way of the Son of God into the Far Country.”1 I will try to show how, despite certain passages that promise otherwise, Barth’s rendering of what he calls the concrete history of God for us in Jesus Christ that constitutes the content of reconciliation—indeed, of the gospel—is framed by the very generalities that Barth claims to reject. These generalities continually function to eclipse Barth’s efforts at concreteness, such that his Son of God ultimately does not journey far enough—or concretely enough—into the far country.

The fourth volume of Barth’s Church Dogmatics is formally called The Doctrine of Reconciliation, but this is also where Barth unfolds the full dimensions of his mature Christology. This is because, for Barth, Jesus Christ is the reconciliation of God and the human creature. To speak of Jesus Christ is to speak of reconciliation; to speak of reconciliation is to speak of Jesus Christ. Barth’s welding together of Christology and reconciliation meant rejecting the theological tradition of separating Christology (who Jesus is) from soteriology (what Jesus does, or what is done in Jesus) as separable doctrines. This is both a classic illustration of Barth’s Christocentric concreteness and of the fundamental structural limitation of that concreteness.

In the first part of Barth’s Christology cum doctrine of reconciliation, he speaks of the Son of God journeying into the far country. The far country refers to the creaturely human reality God takes on in the incarnation; it is the “in the flesh” part of “God with us in the flesh.” The “far” of “far country” signifies the radical extent of divine self-humbling and self-emptying this involves, and so the radical lengths to which God goes to be with and for the human creature, to claim and redeem the human creature as a worthy and faithful covenant partner. The obvious point: God stops at nothing, stops short of nothing, risks everything, goes as far as one can go and then some—into the very jaws of death and through the gates of hell itself—for the sake of the creature and their redemption from the destructive bonds of sin.

One would expect, then, given Barth’s commitment to Christocentric concreteness, that the divine journey to the far country would signify more than simply touching down on human soil in a general way, becoming human in the way one says one has been to a foreign country because of a one-hour layover between flights during which one never leaves the airport. Going further, one would expect God’s becoming human to entail more radicality and risk than leaving the airport via limousine heading straight to the royal palace and its luxurious gated environs, as if the palace would serve God’s purpose just as well as a manger or a jail cell, as if any place—and any company—in this foreign country would do just as well as any other for God’s work of reconciliation, foreclosing the yawning abyss between this particular God and the far country.

Indeed, if one takes Barth’s talk of Christocentric concreteness seriously—in light of passages like the one we have seen cited by Cone, where Barth speaks of God’s taking sides, of showing up in a particular place and among particular company within the conflictual and diverse landscape of history, with and for the denied and deprived of history and against the powerful and privileged—one would be forgiven for expecting that concreteness to entail God’s taking sides in the conflicts determining the internal landscape the far country, beyond simply covering the vast distance necessary to arrive at the far country.2 And not taking just any side. For there is a very particular further distance for the Son of God to go: past the palace, past the houses of parliament, past the 5-star hotels, past the plantation houses, past the gated communities and the mega-church campuses, past the seminaries . . . to the leper colony, the shanty town, the segregated ghetto, the blighted neighborhood, the tent community under the freeway overpass, the holding pen for undocumented migrants at the border—that is, to the non-places and forgotten spaces to which the denied and deprived, the outcast and forgotten, the colonized and enslaved, the marginalized and denigrated citizens (or non-citizens) of the far country are relegated. One might expect that it is to arrive here, here and nowhere else, and in this particular company and none other, that the Son of God journeys to the far country; to take up and inhabit the conditions in which these particular inhabitants of the country live and be counted as one of their company—in their difference from and struggle against the privileged and powerful—as the only possible place and the only possible company proper to God’s being and work of reconciliation in and for that country. That is, one might expect to encounter the divine blackness defined by Cone’s theology and revealed to be inherent in the kind of radical Christocentric concreteness Barth claims to embrace.

And as Cone has already shown us, Barth does not disappoint—at least not completely. There is a thread of passages through Barth’s Christology cum doctrine of reconciliation where he both identifies this particular concreteness of God’s being with us in the flesh and continually insists that it is “not accidental” but inescapably necessary to both God’s identity and work of reconciliation.3 For example: “The affinity of Jesus” is not with “the religiously, morally, politically and socially vital and exalted and triumphant in this world.” Rather, it is with “the weary and heavy laden . . . those who are at the end of their own resources.” Consequently, it is “not the former, but the latter [who] are His people, in whom he can see Himself again and again and to whom He for His part can give Himself to be known as savior and prove himself as such.”4

However, there are many more—and ultimately more decisive—passages in the light of which this concreteness is eclipsed. It is moved to the background, cast in a strictly supporting role in relation to the kind of general schema, constituted by general concepts, that Barth says he rejects: the general schema of reconciliation as an event between two opposing parties—God on one side and (sinful) humanity on the other. In Barth’s language of the far country, the distance between God and the shore of the far country eclipses the distance between the palace’s gated luxury and the segregated, impoverished ghetto/colony (to use Cone’s language) within the far country. What is lost from view are all the very real ways in which, concerning the palace, the ghetto/colony may as well be another, still further country: a still further far country in or of the far country.

As a result, the fact that the Son of God, in journeying to the far country, chooses to journey all the way to the ghetto/colony in the farthest corner of the far country, rather than stopping conveniently at the palace; the fact that, in this journey, the Son of God does not stop short of taking up the concrete existence of the inhabitants of the ghetto/colony in all its conflictual opposition to life on the palatial throne, as nothing less than the necessary expression of God’s own essential identity—none of this is finally allowed to impact the substantive content of the reconciliation accomplished by this journey in Barth’s doctrine of reconciliation. The content of Barth’s doctrine of reconciliation begins and ends with the reparation of the broken relational distance between two parties: God (in general) on one hand, and the human being (in general) on the other. “Reconciliation is God’s crossing the frontier to man . . . on one side there is God . . . and on the other side there is man . . . the sinner . . . who in the flesh is in opposition to Him.”5 In the light of this general schema framing and governing Barth’s doctrine, the broken relational and material distance between the concrete life of the palace and of the ghetto/colony remains untouched by the work of reconciliation. Because the identity of Jesus Christ in Barth’s doctrine is first and finally determined as the mediator between God, on one hand, and humanity-in-general, on the other, the act of reconciliation that unfolds in that schema and through that Jesus appears to leave Caesar comfortably in his palace, worlds away from the colonized peoples who are in turn left to continue languishing under the brutal power of his throne.

The far country itself, then, becomes a general category as Barth employs it in his doctrine. It signifies sin-bound humanity as such and in general, in relation to which the very real world of difference that exists between the sin-bound palace and the sin-bound ghetto/colony, between Caesar on his throne and the colonized thieves constituting the company of Jesus on Golgotha—“crucified with him,” what Barth insists elsewhere is the first church—appears to make no difference at all.6 And this is what I mean by the eclipse of Barth’s commitment to Christocentric concreteness and so of the divine blackness (as defined by Cone) inherent to that concreteness. They are rendered accidental and incidental to the dogmatic content of both his Christology and his doctrine of reconciliation, in opposition to his own avowed commitment to theological concreteness in all things.

But what if Barth’s Son of God did not merely journey into the far country, but instead, consistent with his demand for Christocentric concreteness and the minority testimony of certain passages, did indeed journey to the far corner of the far country—or the far (i.e., colonized) country of the far country? That is, what if the distance between the palace and the ghetto within—or the colony of—the far country was decisive in determining the distance traveled by the Son of God to the far country? And what if, as a consequence, the work of reconciliation accomplished in this journey was the overcoming not only of the sin separating God and far country as a whole, but also of the sin separating the palace from the ghetto/colony? And what if the former overcoming was only accomplished through, in, and as the latter? Well, then you would have James Cone’s theological witness to the gospel of the black Jesus.

For next time: Before we go on to wrap up our engagement with Barth and Cone by pursuing the above questions a bit further, I will indulge my inner theological nerd and spend the next post looking more closely at the precise theological mechanics of the eclipse of Barth’s Christocentric concreteness revealed here, as it plays out through his entire doctrine of reconciliation.

Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics, Vol. 4, Part 1, trans. G. W. Bromiley (London, UK: T&T Clark, study edition, 2010), 150.

Barth, as cited by Cone: “in the relation and events in the life of his people, God always takes his stand unconditionally and passionately on this side alone: against the lofty and on behalf of the lowly; against those who already enjoy right and privilege and on behalf of those who are denied and deprived of it” (Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics, Vol. 1, Part 1, trans. T. Parker et al (Edinburgh, UK: T&T Clark, 1957), 386–7; my emphasis).

Barth, CD IV/1, 168.

Barth, CD IV/1, 171.

Barth, CD IV/1, 79.

Karl Barth, “The Criminals with Him!” in Deliverance to the Captives (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, reprint edition, 2010), 75.