About the author: Chris Boesel is associate professor of Christian theology at Drew Theological School. His primary interest is the extent to which traditional confessions of faith can be seen to call for progressive socio-political visions and commitments. He is the author of In Kierkegaard's Garden with the Poppy Blooms: Why Derrida Does Not Read Kierkegaard When He Reads Kierkegaard (Lexington/Fortress Academic, 2021) and Reading Karl Barth: Theology that Cuts Both Ways (Cascade, 2023).

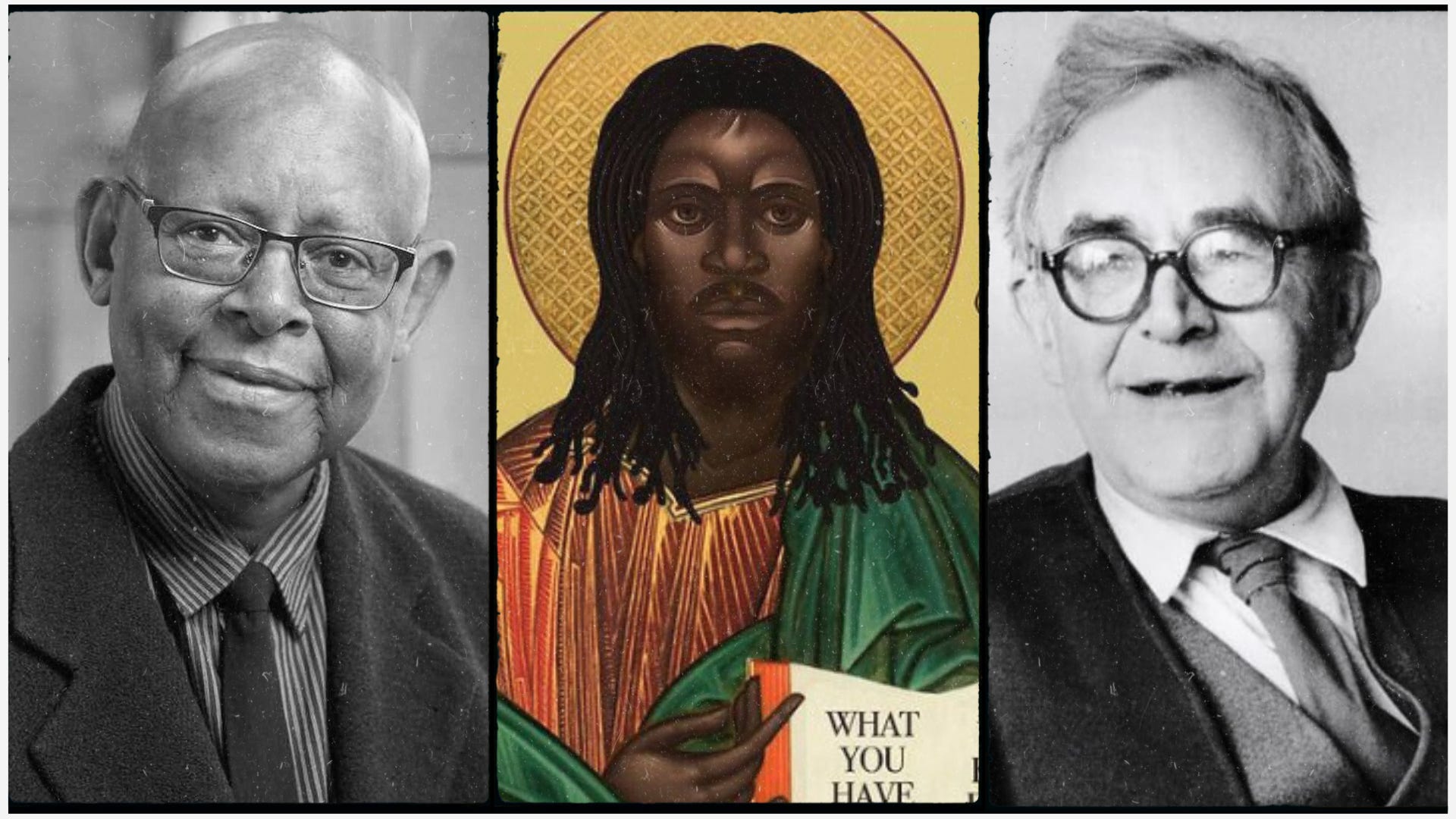

This post is the fourth in a year-long series putting Barth’s theology in conversation with black theological voices. Our primary question: To what extent is Barth’s theology complicit in the silence of white Barthians on racism in the US and to what extent might Barth’s theology function as an anti-racist resource?

In previous posts, I have been looking at the similarities between Karl Barth and James Cone on two theological issues, Christocentric concreteness and the dialectic of divine freedom.

Christocentric concreteness: God is who God is, and we are who we are, in the divine decision, Word, and act made concretely actual in God’s being for the creature in Jesus through the Spirit, the last, first—that is, in the company of those communities unjustly subjected to denigrating, marginalized, and oppressive social conditions.

The dialectic of divine freedom: this scandalous reality of God’s being radically for the creature, in irrevocable identity with the creature, in Jesus through the Spirit, and so showing up in the oppressed and suffering margins of history, is made actual in and through a radical divine initiative and freedom that prevent that identity from ever becoming a creaturely possibility or possession to wield or control.

I ended the last post with a question: Given this similarity in their theologies, why does Barth seem to stop short of recognizing the blackness of the God who is for the creature in this way, in this Jesus and through this Spirit, that Cone makes so clearly visible in the context of a racist USA?

To answer this question, we must first make sure we have a sound understanding of exactly what Cone means by divine blackness.

For Cone, Jesus is black because God is black in God’s essential nature, and Christians know and confess Jesus as God concretely with and for us in the flesh; and Christians making this confession know—check that: should know—God is black because Jesus is black, as he is encountered in the social conditions of his simultaneously full and particular humanity. But what exactly does Cone mean by this blackness of God in Jesus through the Spirit? Is Cone attributing an ethnicity and/or racial category to God’s essential identity that is then expressed in the concreteness of Jesus’s humanity? Is God’s essential identity uniquely linked with those human communities of African descent? Well… yes and no.

For Cone, divine blackness has two distinct yet interrelated dimensions. As Cone puts it: “Christ’s blackness is both literal and symbolic.”1

Unlike the normative habits of Anglo-European Christologies, Cone’s Christocentric concreteness does not let us lose sight of the concrete particularity of the humanity of Jesus: the “fully human” part of the Chalcedonian affirmation, “fully human, fully divine;” the “in the flesh” part of the incarnational affirmation, God in the flesh. In particular, Cone keeps our eyes focused on how the specific dimensions of that concrete creaturely particularity place Jesus in a very specific social location, in the company of very specific communities within the wider conflictual landscape of his historical context.

For Cone, Jesus’s Jewish identity is an essential dimension of this concrete particularity: it is “because he was a Jew,” that we can—and must—now say that “Jesus is black.”2 However, for Cone, this is not because of Jesus’s Jewish ethnicity in itself. It is because of the particular social location and accompanying historical experience of Jesus’s Jewish community in the conflictual complexity of that historical context. It is because Jesus was a poor, marginalized Palestinian Jew, there and then, on the margins of a community with a history of slavery that was currently suffering under the colonial bootheel of what we would now call the European empire—a political regime that eventually executed him as a threat to law and order—that we can and must recognize the risen Jesus alive and present for us today as black, here and now, in the context of a racist USA.

The use of the term “black,” then, to name the identity of the risen Jesus for us today, in the present context of a racist USA, arises contingently from the particular identity of the community in the US context whose imposed social location and experience bears an uncanny and undeniable resonance with that of the biblical Jesus and his Jewish community—and the dangerous, vulnerable company he sought out on the margins of that community.

This is what Cone means by the literal dimension of divine blackness: Because the social location and condition of marginalization and subjugation imposed upon the black community in a racist USA is based on the racial category of blackness, it is precisely with that blackness that God identifies Godself when identifying with the denied and deprived—i.e., with those whose social location is one of marginalization and subjugation. This is the “yes” part of the “yes and no,” above. There is real identification between God and the African American community in their struggle against racist oppression, and with any BIPOC community in contexts of white supremacy wherein skin color and the racial category of blackness are primary identity markers targeted for subjugation and harm.

For Cone, the literal dimension of divine blackness is real, but in a contingent way. As contingent, the literal dimension of divine blackness is contextually dependent. God’s blackness is a literal reference to the black community, and to the blackness of the black community, in particular contexts of white supremacy where the racial category of blackness is used to justify the social, political, and economic marginalization and subjugation of that community. But what about those contexts wherein the forces of marginalization and subjugation are not primarily deployed and justified on the basis of skin color and the constructed racial category of blackness?

This brings us to Cone’s view of the symbolic dimension of divine blackness, and returns us to the pivotal concept of social location. Blackness functions symbolically when pointing to God’s identity with and commitment to any and all communities subject to social locations of marginalization, oppression, and suffering, whether or not those communities are targeted for subjugation on the basis of skin color and the racial category of blackness.

This symbolic function of divine blackness allows it to travel across contexts, to signify God’s identity with different oppressed communities in different contexts. As Cone puts it: “I realize (sic) that ‘blackness’ as a Christological title may not be appropriate in the distant future or even in every human context in our present”; it “is not simply a statement about skin color, but rather, the transcendent affirmation that God has not ever, no not ever, left the oppressed alone in struggle [be they oppressed on the basis of skin color or not]. He was with them in Pharaoh’s Egypt, is with them in America, Africa and Latin America.”3

For Cone, then, the blackness of God in Jesus through the Spirit is a symbol of God’s identity with the oppressed that is, at the same time, literally tied to the racial categories of skin color within contexts determined by racism and white supremacy (which, let’s face it, can be seen to apply in some way to pretty much every context, globally, given the continuing extent of the economic and cultural as well as political dimensions of western influence) but whose symbolic function is not limited to and is mobile in relation to racial categories of skin color. It names a particular social location, condition, and existence—one of denigration, vulnerability, marginalization, and oppression; a social location that can be imposed upon any number of communities by the normative forces of any society wielding the structures of power to target minoritized communities for harm.

Cone’s theological logic, then: If the concreteness of Jesus’s humanity there and then, in all its historical particularity, is taken seriously, then the blackness of God for us in Jesus (through the Spirit) today, here and now cannot be avoided. If the concreteness of God with and for us means that Jesus Christ is the revelatory and redemptive Word of God to and for creatures and all creation, then that Word of God is black in the two-fold way intended by Cone’s employment of divine blackness: functioning literally in contexts of white supremacy, because it functions symbolically in every context.

For next time: This returns us to our question that ended the previous post: Given the similarities between Cone and Barth on the Christocentric concreteness informing their visions of Jesus Christ as the Word of God, why does Barth seem to stop short of recognizing the blackness of this Word of God that Cone makes so clearly visible in the context of a racist USA? And do the reasons justify that omission and therefore lay the erasure of divine blackness by Barthians in the US context fully at the latter’s door? We will pick up this question in the next post.

James H. Cone, God of the Oppressed (Maryknoll: Orbis Press, 1997), 125. Regarding Cone’s Christocentric concreteness, see: “The norm for all God-talk that seeks to be black-talk is the manifestation of Jesus as the Black Christ who provides the necessary soul for black liberation” (James H. Cone, A Black Theology of Liberation [Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 2010], 80); “. . . Jesus Christ, in his past, present and future, reveals that the God of scripture and tradition is the God whose will is disclosed in the liberation of oppressed people from bondage” (Cone, God of the Oppressed, 127).

Cone, God of the Oppressed, 123.

Cone, God of the Oppressed, 123, 126. For a critical reading of Cone’s use of the term “ontological blackness” in relation to his two-fold form of divine blackness, see Victor Anderson, Beyond Ontological Blackness: An Essay on African American Religious and Cultural Criticism (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016).