Theologizing Beyond State Violence, Part 3

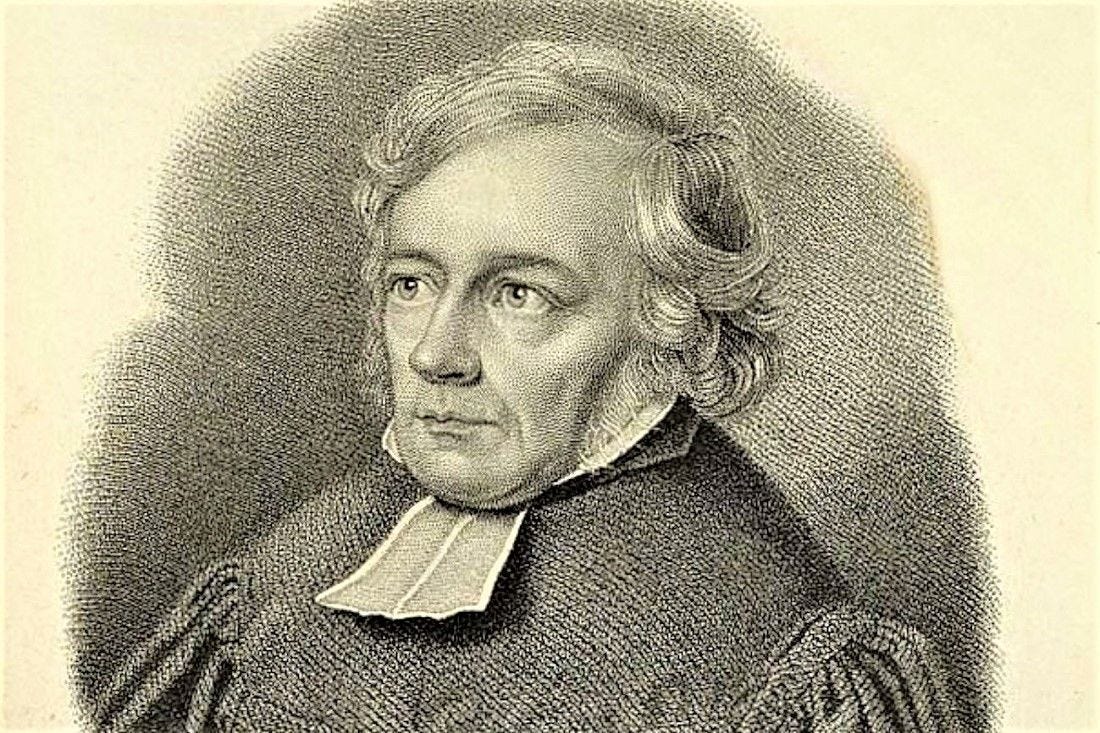

Schleiermacher, Free Sociability, and Thinking Beyond State Violence

About the author: Christopher Choi is currently a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Virginia. His research engages modern religious thought, the philosophy of religion, and Black Studies. Most recently, his dissertation critically examined the intersection of philosophical and theological doctrines of state power with antiblackness and discourses on slavery. His scholarly interests include political theology, the theology of James Cone and Karl Barth, the thought of W. E. B. De Bois, German idealism and Romanticism, and modern Jewish philosophy.

In my last few posts, I focused on Karl Barth’s theological response to the destruction and violence of the World War and the revolutionary movements in its aftermath. I presented this moment of Barth’s life as an analog of our own insofar as we, like him, are confronted by the theological challenge posed graphically in state violence. Barth perceived militarism, state power, and revolution as (geo)political problems and, perhaps more fundamentally, theological problems. I noted what I think are constraining factors in Barth’s thought. Namely, his linkage between sociopolitical possibility and the state seems to be an obstacle to shedding light on and exploring what I described as stateless and fugitive possibilities. I made the case that we, like Barth, must critically reexamine theological conceptions of social life and their relationship to conceptions of state power and violence.

In this third piece, reaching further back in time may be worthwhile. In pursuit of theologizing beyond state violence, I suggest shifting focus from Barth’s twentieth-century confrontation with the socialist revolution to Friedrich Schleiermacher's early writings over a century earlier. Like the former, Schleiermacher’s early writings intersected with wrestling over the question of revolution.

Schleiermacher was deeply impacted by and closely followed news of the revolutionary upheaval in neighboring France. While supporting what he viewed to be the noble ideals of the French Revolution, Schleiermacher joined his Prussian contemporaries in growing dismay and anxiety toward news of mass and senseless state violence. These concerns show up in his 1799 edition of On Religion: Speeches to its Cultured Despisers, where he expresses his wish to avoid the “great convulsions” in France.1 It is also apparent that Schleiermacher viewed the revolution, with all its messiness, as posing profound questions impossible to ignore. The world could no longer be the same. “These [are] times of universal confusion and upheaval,” he writes, in which “nothing remains unshaken.” What was once taken for granted, assumed as stable foundations, seems to be “on the verge . . . of sinking in the universal maelstrom.”2

Schleiermacher departs from Karl Barth, however, in how he responds to the questions posed by revolutionary upheaval. His contending with the events in neighboring France coincided with a burgeoning interest in the idea of human sociability [Geselligkeit]. What strikes me in his fascination and experimentation with sociality is his explicit turn away from what he viewed as the mechanical and lifeless form of the present state. The “earthly political bond,” which he argues the cultured despisers overestimate, is “forced, transitory, and provisional.”3 He reaches for a language of social possibility and life that moves beyond the coercive logics of the state. Ultimately, he locates this possibility and life in the “wholly different form of sociability” unique to religion.4

I argue that Schleiermacher’s ecclesiology opens us to think about forms of sociality beyond the logic of state violence. His relative pessimism toward the state coincided with a burgeoning and avid interest in religious formations of a different kind of “society” [Gesellschaft], taking the shape of what he calls “free sociability.” Here, each “full of their own power,” the hierarchies and asymmetries of the larger society are replaced with the “most cordial unanimity of each with all and of the most perfect equality, a mutual annihilation of every first and last and of all earthly order.”5

Especially interesting in Schleiermacher’s account is his characterization of free sociability as unbound and unregulated by an externally imposed law or purpose. It does not rely on any official force or authority [eine öffentlichen Gewalt]. Rather than relying on policing or external coercion, free sociability is sustained by free-flowing and reciprocal interaction. Rather than a cog in a machine, in free sociability, members engage in an uninhibited “free play of their thinking and feelings,”6 where “all members stimulate and enliven one another.”7 Rather than an abstract and interchangeable unit, each presents its irreducible individuality and is viewed as a unique expression of the divine. “Each individual,” he writes, “should represent humanity in their own way.”8

The social theory of Schleiermacher’s ecclesiology also calls attention to and highlights the importance of how bodies are arranged and interact across space. Certain formations of space establish and cultivate distinct kinds of sociability. For example, according to Schleiermacher, ballroom dancing is not conducive to free sociability since it restricts meaningful interaction between the two dance partners. He is also not fond of the drama, which, while engaging all participants, constitutes a one-directional dynamic since the audience is passive and incapable of reciprocating. Schleiermacher, at least indirectly, has in mind here the kind of gatherings and social interaction he experienced in the salons of Berlin, particularly the one facilitated by his friend Henriette Herz, which included women and emancipated Jews such as herself.

Schleiermacher’s On Religion: Speeches to Its Cultured Despisers, however, suggests a subtle criticism of the so-called “cultured” [die Gebildeten], not only in regards to their patronizing views of religion but also consequently their short-sighted view of human sociability. It is not salon culture but religion that proves to be the perfect host for free sociability. Free sociability is, for Schleiermacher, perfectly depicted in an unassuming and intimate liturgical gathering. Individuals arise from the “free stirring of the spirit” and share their intuition of the divine as the congregation “follows his inspired speech in holy silence.” The congregants share in “audible confession of accord” and sing hymns together.9 Free sociability looks like Schleiermacher’s Christmas Eve Celebration: A Dialogue, which describes a celebratory gathering of family and friends within a home where the voices of religious skeptics are welcomed, women challenge patronizing masculinity, and the role of children is centered.

I am not suggesting that Schleiermacher attached radical politics or insurgent significance to religious sociality. True religion, Schleiermacher writes, “would not even want to reign in a foreign kingdom, for it is not so desirous of conquest that it wishes to enlarge what is its own.”10 Rather than interfere with or compete with the political sphere, religion complements and accompanies it “like a holy music; we should do everything with religion, nothing because of religion.”11 Further, Schleiermacher’s elevation of “propriety” and “refinement” in his writings on free sociability seems to suggest that the gatherings he is envisioning are in cultured and urbane settings and certainly not what one would conventionally call “rebellious” or “revolutionary.”

I am suggesting that Schleiermacher’s social theory and theology help raise the question of the relationship between social life and state violence and provide an opening to explore the possibilities of social life beyond that violence theologically. We can learn from his intellectual curiosity in sociality and his attentiveness to how different spatial formations induce different social interactions. I argue that his idea of the free sociability of religion highlights the relevance of ecclesiology for thinking about radical forms of sociality. In these ways, Schleiermacher’s writing offers a generative space for exploring a theology of sociality beyond state violence.

Friedrich Schleiermacher, On Religion: Speeches to its Cultured Despisers, trans. Richard Crouter (Cambridge University Press, 2008), 91. Open access version: https://archive.org/details/onreligionspeech00schluoft/page/n5/mode/2up

Schleiermacher, On Religion, 56.

Schleiermacher, On Religion, 75.

Schleiermacher, On Religion, 79.

Schleiermacher, On Religion, 75.

Friedrich Schleiermacher “Monologen: Eine Neujahrsgabe,” in Schriften aus der Berliner Zeit 1800–1802, ed. Günter Meckenstock. Kritische Gesamtausgabe, vol. 1.2 (Walter de Gruyter, 1984), 172. “. . . das freie Spiel seiner Gedanken und Gefühle . . .”

Friedrich Schleiermacher, “Theorie des geselligen Betragens,” in Schriften aus der Berliner Zeit 1796–1799, ed. Günter Meckenstock, vol. 1.2, 168.

Schleiermacher, “Monologen: Eine Neujahrsgabe,” 18.

Schleiermacher, On Religion, 75.

Schleiermacher, On Religion, 16.

Schleiermacher, On Religion, 29.

Seeing this article caused me to go back and look at the other two in the series, and I am so glad I did. Like yourself Dr. Choi, the murder of George Floyd and its aftermath caused me to wrestle with God to discern a theological response to state violence and more specifically police brutality. Within 12 months I wrote an award-winning book, From Scapegoats to Lambs How God's Word Speaks to George Floyd's Murder, that examines numerous biblical passages to show how a theology of scapegoating informs how police justify the excessive use of force. When I presented a paper based on the book at a regional AAR meeting last year, it won an award and the conveners compelled me to go further, so now I am enrolled in Ph.D. studies in Theological Ethics at UNISA. My dissertation is focused on the theology of scapegoating but your series will certainly enrich my research immensely. I also believe an article on the theology of Dietrich Bonhoeffer (and of course Rene Girard, the founder of the scapegoat principle) could add to this series. THANK YOU!