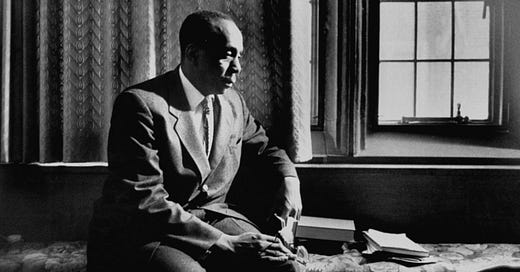

About the author: Jason Oliver Evans is a research associate and lecturer at the University of Virginia. He is a constructive theologian working at the intersection of Christian systematic theology with theological and social ethics, Africana studies, and studies of gender and sexuality. Evans completed his dissertation on the person and work of Jesus Christ through critical engagement with key texts by Karl Barth, James H. Cone, Delores S. Williams, and JoAnne Terrell. Drawing upon these authors, Evans renders overall a constructive Black queer theology of atonement and Christian life.

What is the significance of Jesus of Nazareth for those who find themselves “stand[ing] with their backs against the wall?”1 In other words, who was Jesus, and what difference does he make for minoritized and marginalized peoples? 20th-century Baptist pastor, mystic, and theologian Howard Thurman’s attempt to answer this question, outlined in his acclaimed book Jesus and the Disinherited, grounds this rumination in African American Christological reflection in conversation with Karl Barth. Drawing insights from each author, this post argues that in Jesus Christ—the Man from Galilee—those who are “the disinherited” and struggle to make sense of their place in a complex world may find life, strength, courage, and love. In this Man, we find none other than Deus pro nobis—the God who is for us!

In Jesus and the Disinherited, Thurman sets out to offer an interpretation of Jesus that counters the seemingly inept, even harmful, iterations of American Christianity. “To those who need profound succor and strength to enable them to live in the present with dignity and creativity,” Thurman contends, “Christianity often has been sterile and of little avail.”2 The tragic irony is that for a movement that began among an oppressed minority group, Christianity has become an established religion of the powerful and elite. By becoming a religion of the strong against the powerless, Christianity, especially in its modern configuration, has “lost the plot,” so to speak. In other words, the religion throughout its history has abandoned what Thurman calls “the religion of Jesus.” By this elusive phrase, Thurman aims to capture the centrality and uniqueness of Jesus’ way of life and message, that is, the kingdom of God; thus, Jesus stands out from the rest of his peers as a radically exemplary figure who the disinherited may follow and in whom they may find inspiration and courage.

Given the history of American chattel slavery and racial domination, many African Americans grew suspicious of the Christian faith. For some, including Thurman himself, the traditional Christian understandings of salvation had become unintelligible and have little to say to them both as modern people and as they struggle to find freedom from oppressive forces.3 The form of Christian piety they reject can be described either as “other-worldly” (like Thurman does) or, less acerbic, “compensatory.”4 This form of piety emphasizes the achievement of salvation in the world to come and God’s provision of spiritual blessings for those who languish under oppressive structures. It also emphasizes personal holiness. However, Thurman calls for what some scholars of Afro-Christianity call a “constructivist” interpretation of the Christian faith.

Constructivist interpretations emphasize African Americans’ agency in combating the sinful social structures under which they endure.5 Against an “other-worldly” construal of the Christian religion, Thurman insists, “the religion of Jesus appears as a technique of survival for the oppressed.”6 Salvation, then, for Thurman, is oppressed peoples’ literal participation in Jesus’ unique way of living such that by following him, they too can overcome what Thurman calls “those hounds of hell:” fear, deception (hypocrisy), and hatred.7 Therefore, the situation of the disinherited requires a fresh reading of the Gospel story to retrieve the religion of Jesus.8

According to Thurman, three facts are pertinent for understanding the religion of Jesus. First, that Jesus of Nazareth was a Jew. He writes, “It is impossible for Jesus to be understood outside of the sense of community which Israel had with God.”9 One of the failures of the Christian church is that it severed this connection between Jesus and the story of Israel. For Thurman, one cannot fully appreciate the life and teachings of Jesus if they do not, at the same time, take seriously the miracle of God’s dealings with Jesus’ people. Jesus’ unique, exemplary life is best understood as an intensification of and an outworking of God’s saving/liberating activity in Israel’s own life:

Here is one who was so conditioned and organized within himself that he became a perfect instrument for the embodiment of a set of ideals—ideals of such dramatic potency that they were capable of changing the calendar, rechanneling the thought of the world, and placing a new sense of rhythm of life in a weary, nerve-snapped civilization.10

The second fact is that Jesus was a poor Jew. As the gospel records reveal, Jesus was born into a poor family.11 According to Thurman, what is more important is that Jesus’ economic condition indicates his identification with the overwhelming majority of the earth’s population, which languishes in poverty. It is this fact that truly reveals Jesus’ identity as the Son of Humanity/Human One.12 Third, Jesus was born as a member of a minority group that suffered under Roman imperial occupation. Thurman finds a striking parallel between the situation of Jesus in Palestine and the situation of American Americans living in the United States in the wake of chattel slavery. These three facts provide the necessary but insufficient context for understanding Jesus’ life and work among the disinherited. Considering these facts in and of themselves are inadequate because although he experienced the same religious, cultural, and political situation as his fellow Jews, Jesus stood out from among them as a supremely unique individual whose psychological and spiritual disposition yielded an exemplary life that drew others in his orbit to listen and follow him.

But who does Thurman say that Jesus is? Frankly, Thurman leaves that question unanswered. He does not make any confessional, even dogmatic Christological statements. Thurman sets aside traditional understandings of Christ and salvation for fear that they offer no relief for the disinherited. And yet, Thurman seems to invite the disinherited to answer this question for themselves, and, after careful consideration of the religion of Jesus—following his teachings and walking in his way—the disinherited may encounter the Eternal who enfolds their lives, loves them, and, consequently they recognize and affirm themselves as children of God.

Remarkably, Thurman’s meditation on the life and teachings of Jesus reminds me of what I find deeply compelling about the work of Karl Barth. While both men hail from different racial, social, confessional, and national backgrounds, I find that both Thurman and Barth preoccupy themselves with attending to the ratio of Christian faith. However, they differ in their starting points methodologically. Thurman starts his Christological reflection considering the so-called “Jesus of history.” What is clear for Thurman is that the facts of Jesus’ history matter, but one does not stop there. One can intuit the significance of his person by following his powerful teachings and example. However, Barth begins head-on with the doctrine of the Incarnation, affirming that Jesus of Nazareth is none other than the Word of God who became flesh (Jn 1:14).13 Of course, in his mature Christology,14 Barth does affirm that the living Word became Jewish flesh. Barth would agree with Thurman that one cannot truly understand the significance of Jesus’ life and teachings apart from the history of Israel. Like Thurman’s, Barth’s Jesus has total solidarity with the people of Israel. And yet, Barth wants us to understand that Jesus’ history is God’s history in a way less elusive and perhaps more “metaphysical” than Thurman would allow.

For Barth, the Incarnation is the event, happening, and occurrence of the eternal Son’s self-humbling descent into the sin-controlled situation of human beings in desperate need of salvation. Indeed, in the descent of the living Word, Jesus is the Messiah of Israel and the Savior of the whole world. Still, Barth’s Christology seemingly betrays the type of salvation that Thurman suspects does not help the disinherited. However, I would wager that this may be a misunderstanding of Barth’s central point. Jesus Christ can and does have full solidarity with his people, Israel, because he is also the living Word who freely chooses to assume the essence and existence of God’s creature. However, we cannot stop there! Thurman is right to emphasize that Jesus was a poor and oppressed Jew. Thus, Jesus understands the troubles his people and African Americans have seen through the years. By joining both Thurman and Barth’s insights together, we can further understand and affirm that the God revealed in Jesus of Nazareth—the Man from Galilee—is the Holy One who has come into the world to overcome the fallen human condition in all of its dimensions—social, political, personal, ecological, cosmic—by assuming the condition of the oppressed (sinned-against) and oppressor (sinner) alike. By doing so, Jesus addresses both groups with the good news of salvation and liberation for all. In short, Thurman and Barth find in Jesus the God who is for us!

For Further Reading:

Barth, Karl. Church Dogmatics. Translated by G. T. Thomson. Edited by Geoffrey Bromiley and Thomas F. Torrance. 5 vols in 14 parts. Hendrickson Publishers, 2010. First published 1936–1977 by T&T Clark.

Floyd-Thomas, Stacey, Juan Floyd-Thomas, Carol B. Duncan, Stephen G. Ray Jr., and Nancy Lynne Westfield. Black Church Studies: An Introduction. Abingdon Press, 2007.

Thurman, Howard. Jesus and the Disinherited. Beacon Press, 1996. First published 1949 by Abingdon Press.

Howard Thurman, Jesus and the Disinherited (1949; reis., Beacon Press, 1996), 1.

Thurman, Jesus and the Disinherited, 1.

Thurman, Jesus and the Disinherited, 18.

For further explanation of compensatory/accommodationist piety in Afro-Christianity, see Stacey Floyd-Thomas et al., Black Church Studies: An Introduction (Abingdon Press, 2007), 86–87.

Floyd-Thomas, Black Church Studies, 87–88. Thomas et al. note that compensatory/accommodationist piety and constructivist piety are not necessarily mutually exclusive nor form a dichotomy between the sacred and secular.

Thuman, Jesus and the Disinherited, 18.

Thuman, Jesus and the Disinherited, 18–19.

Thuman, Jesus and the Disinherited, 5. Thurman writes, “It is necessary to examine the religion of Jesus against the background of his own age and people, and to inquire into the content of his teaching with reference to the disinherited and underprivileged.”

Thurman, Jesus and the Disinherited, 5.

Thurman, Jesus and the Disinherited, 6.

Thurman, Jesus and the Disinherited, 7. Specifically, Thurman references the dedication of Jesus at the temple record in Luke’s account (Lk. 2:22–24). Mary, Jesus’ mother, sacrifices two turtle doves or pigeons, thus inferring that she and Joseph could not afford to bring a lamb, which is primarily required for a burnt offering (see Lev. 14:22).

Thurman, Jesus and the Disinherited, 7. Thurman, however, does not explain the connection between Jesus’ poverty and his identity as the Human One.

See Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics, Volume I: The Doctrine of the Word of God, Part 2, trans. G. T. Thomson and Harold Knight, eds. G. W. Bromiley and T. F. Torrance (1956; reis., Hendrickson Publishers, 2010), 123–202.

See Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics, Volume IV: The Doctrine of Reconciliation, Part 1, trans. G. W. Bromiley, eds. G. W. Bromiley and T. F. Torrance (1956; reis., Hendrickson Publishers, 2010), 166f.