About the author: Tim Hartman is Associate Professor of Theology at Columbia Theological Seminary. He is the author of two books: Theology after Colonization: Kwame Bediako, Karl Barth, and the Future of Theological Reflection, and Kwame Bediako: African Theology for a World Christianity. He is an ordained minister in the Presbyterian Church (USA). His scholarly interests include contemporary Christian theologies worldwide, Christology, Lived Theology, Election/Predestination, antiracist theologies, ecclesiology, postcolonial mission, and the work of Karl Barth, Kwame Bediako, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, and James Cone.

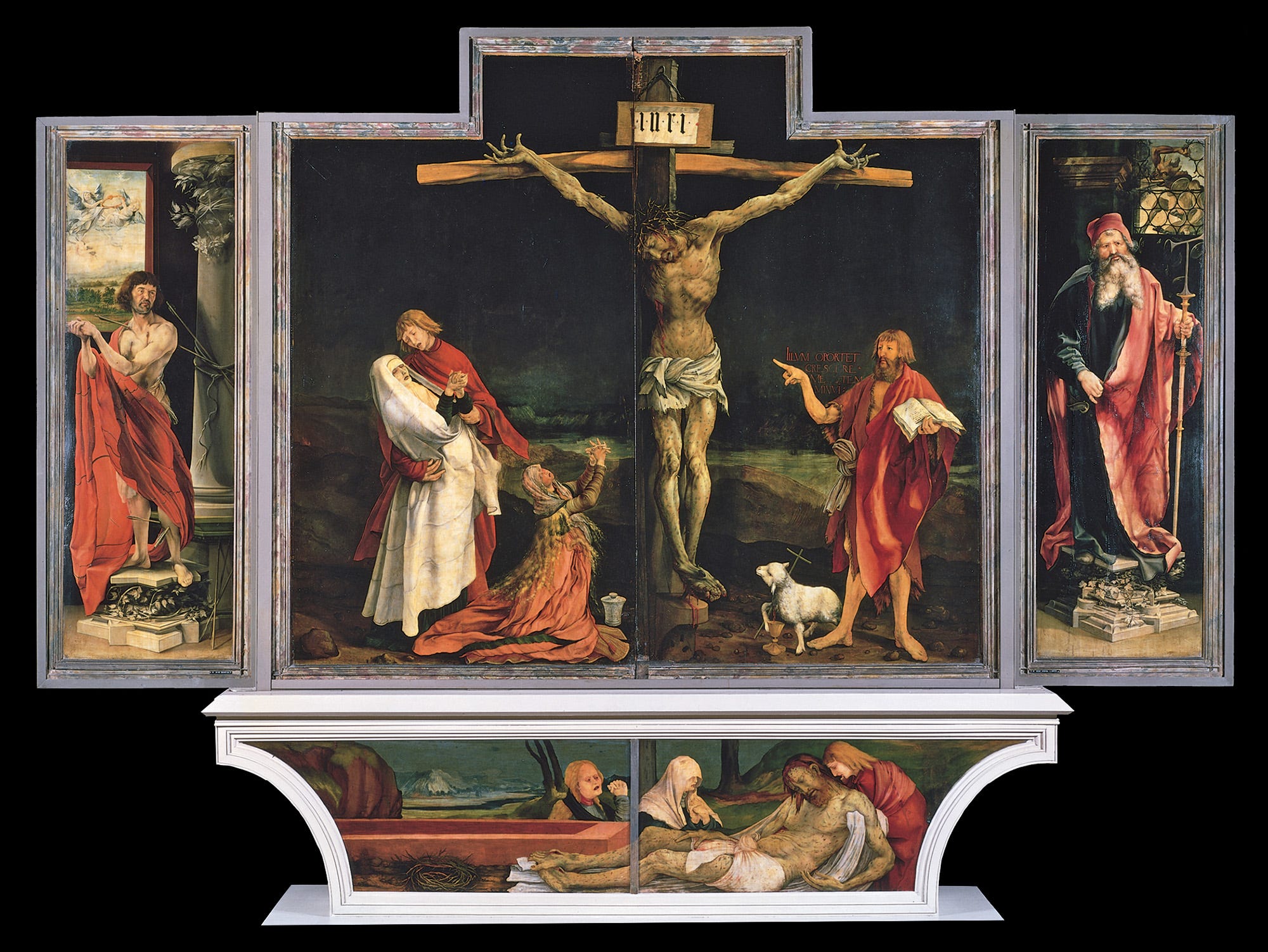

For nearly fifty years, Matthias Grünewald’s painting of the crucifixion of Jesus Christ hung above the desk where Karl Barth worked. In Barth’s 1920 essay, “Biblical Questions, Insights, and Vistas,” he draws attention to the bony hand of John the Baptist, pointing to Christ on the cross.1 Eberhard Busch believed that Barth wanted his theology to point to Jesus just like the Baptist’s hand that all proper theology must be like that hand.2 My interest here is not in the painting’s portrayal of the Baptist’s finger, but in the lamb at his right foot. The lamb is holding a cross while its blood drains into a chalice.

Barth does not devote a lot of space to the imagery of Jesus Christ as the Lamb of God. However, in two small print sections of §51.2, “The Kingdom of Heaven,” Barth cites Revelation 5 in which the slain lamb opens the scroll sealed with seven seals.3 Barth identifies, “this Lamb [as also] the Lion, the all-powerful and all-wise Executor of [God’s] will and plan.”4 Later in §70, “The True Witness,” Barth writes that “The Lamb slain not only stood, but still stands, between the throne of God and the heavenly and earthly cosmos (Rev. 5:6), and according to the song in this chapter He not only was but is worthy to open the book and the seals, and to receive power and riches and wisdom and strength and honor and glory and blessing.”5

The Lamb (especially as described in Revelation 5) is worthy for 3 reasons.6 First, the Lamb is worthy because he was executed, or slaughtered. The Lamb, who is also described as the Lion of Judah, does not earn his place by conquering with might, but by being slaughtered like a Lamb. The Lamb conquered, but not in a lion-like way. The slaughtered lamb immediately recalls the book of Exodus and the last plague when the angel of death passed over the homes of the Israelites who had slaughtered a lamb and put the blood on their doorposts. (Grammatically, the lamb “slaughtered” for us is in ‘the perfect tense’ to convey the continuing effects of a once-for-all act.) There is a parallel here to the first Passover, but instead of protecting one people (the Israelites), the blood of this lamb ransomed and set free all peoples, from every tribe.

Second, the Lamb is declared worthy because he used the blood of his execution to ransom, or purchase, all people. The lamb is not worthy because he was slaughtered; the lamb was slaughtered because he was worthy. The life of Jesus made him worthy of worship. The life of Jesus led to his slaughter. When Jesus was raised from the dead, death was conquered, and Jesus lived again. The slaughtered Lamb is an image of the resurrected Jesus, with holes in his hands and his side. The lamb was killed for living a righteous life. In this way, Christians worship the “alive-again” lamb.

In the words of African-American New Testament scholar, Brian Blount, John (the presumed author of Revelation) “hears ‘lion,’ but sees a Lamb. Whenever hearers/readers see the Lamb in the remainder of the narrative, the staging of…[Revelation] chapter 5 suggests that they hear the footsteps of a lurking Lion.”7 In this way, the Lamb is not in contrast to the Lion, but instead is an extension of the same powerful figure. The slaughtered Lamb is a powerful conqueror. Barth articulates these connections: “For the power of God Himself, reflected in the power which He gives to man, is the power of Jesus Christ, and therefore the power of the Lamb as well as the Lion, of the cross as well as the resurrection, of humiliation as well as exaltation, of death as well as life.”8 We worship a slaughtered Lamb—with the power of a lion, but who does not use a lion’s tactics or methods.

Third, through his actions and slaughter, the Lamb establishes God’s believers as a reign of priests on earth. We are blessed. Not for ourselves, but to be a blessing to others, to the whole world. Our worship is to overflow into the world. In the concluding verses of Revelation 5, the Lamb continues to be praised and worshiped. The imagery here is of final redemption and salvation, which is not just about individual souls, but requires that the entire world be free of suffering and oppression.

Roman Catholic theologian Elizabeth Johnson reminds us that “The symbol of God functions.”9 What she means is that how we think about God, especially how we imagine God, affects how we live in the world. While Johnson reflects on what has happened when God is presented exclusively as male, her insight on the power of symbolism applies here as well: do we see our God primarily as a Lion, or as a Lamb? Do we believe that ultimate power comes from size, strength, might, or ferocity? What would it mean to shift our idea of God from a strong, mighty Lion to a Lamb? But not a cuddly, frail lamb, but a lamb who has been slaughtered because of his way of life.

The lamb Jesus was slaughtered because he was worthy. Because of who he was (Son of God) and how he had lived, and that He LIVES. Jesus’ death did not make him worthy. Jesus’ shed blood did not make him worthy. His life was a threat to the Roman Empire, and they killed him. As the South African theologian and anti-apartheid activist Allan Boesak describes Revelation 5: “It is dangerous, heady stuff, this song. It is a freedom song.”10 Human laws, expectations, or customs do not bind the Spirit of God. Jesus’ life of non-violent resistance was not what was expected of the coming Messiah. When Jesus returns in the fullness of time, we should not expect an army, nor a conquering hero. The slaughtered lamb conquered with sacrificial love. This is the God whom we serve, and we are called to live in a similar manner.

Near the end of his too-short life, Martin Luther King named this truth, saying: “Power without love is reckless and abusive…love without power is sentimental and anemic.”11 In the slaughtered Lamb, we see power and love brought together in the Crucified and Risen Lord, Jesus Christ.

We are invited to encounter God in this slaughtered lamb. The Christian faith is not a tool or instrument to apply to our problems. The Christian faith is an invitation to encounter the Living God, symbolized as a slaughtered lamb who lived for us, died for us, was raised for us, and reigns in power for us. Jesus Christ is both the Lion of Judah and the slaughtered Lamb of God. In baptism, we re-enact dying with Jesus and being raised with him to new life. In Communion, we proclaim the death of our Risen Lord until he comes again. And surely he will come, as the slaughtered lamb who has conquered.

Karl Barth, Word of God and Theology, trans. Amy Marga (T&T Clark, 2011), 82.

Eberhard Busch, The Great Passion: An Introduction to Karl Barth’s Theology (Eerdmans, 2004), 6.

Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics III/3 (T&T Clark, 1960), see 449-450 and 469-476.

Barth, Church Dogmatics III/3, 471.

Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics IV/3 (T&T Clark, 1961), 397.

See Brian K. Blount, Revelation (Westminster John Knox Press, 2009), 114–5.

Blount, Revelation, 117.

Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics III/4 (T&T Clark, 1961), 397.

Elizabeth Johnson, She Who Is: The Mystery of God in Feminist Theological Discourse (Crossroad, 1992), 3–4.

Allan Boesak, Comfort and Protest: The Apocalypse of John from a South Africa Perspective (Westminster John Knox, 1987), 60.

Martin Luther King Jr., “Where Do We Go from Here? (1967),” in A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches (Harper One, 2003), 247.