Politicized Imagination

On Christian Identity, the 20th-Century Rwandan Genocide, and the Vices of "Christian" Nationalism

About the author: Tim Hartman is Associate Professor of Theology at Columbia Theological Seminary. He is the author of two books: Theology after Colonization: Kwame Bediako, Karl Barth, and the Future of Theological Reflection, and Kwame Bediako: African Theology for a World Christianity. He is an ordained minister in the Presbyterian Church (USA). His scholarly interests include contemporary Christian theologies worldwide, Christology, Lived Theology, Election/Predestination, antiracist theologies, ecclesiology, postcolonial mission, and the work of Karl Barth, Kwame Bediako, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, and James Cone.

I recently returned from a visit to Kigali, Rwanda, through a partnership between Auburn Seminary and the Aegis Trust. I was honored to be among a cohort of twenty “Auburn Aegis Scholars” who participated with four hundred others in the Listening & Leading Conference: The Art and Science of Peace, Resilience, and Transformational Justice. This visit left me reflecting on questions of Christian identity and the real danger when ideological, cultural, or political ideologies are more powerful than the gospel of Jesus Christ.

Today, Rwanda is a country of 14 million people in central Africa, “the land of a thousand hills” known for exporting coffee to the rest of the world. That said, Rwanda is best known in Europe and North America for the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi, where one million Rwandans were killed in one hundred days. Most often, victims were killed by their neighbors with machetes or clubs. What I find particularly chilling about the events of 1994 is that, in the 1990s, Rwanda was widely considered to be “the most Christian country in Africa,” with approximately 98% of Rwandans identifying as Christians. In addition, mass killings occurred inside over fifty churches; 12% of those killed in the genocide died inside church buildings.1 Myths of “race” and ethnic superiority proved stronger than the Christian faith.

In the 1885 Berlin Conference, borders were drawn around the country of Rwanda—even though none of the Europeans or North Americans present had ever been there—and in 1898, Rwanda became a German colony. Then, following the German defeat in World War I, the League of Nations stripped Germany of its colonies, and Rwanda became a mandate territory of the League of Nations under the administration of Belgium. As the Belgians arrived, they discovered that the Rwandans all spoke the same language, shared the same culture, and shared similar physical characteristics as well. In short, they were one people. Yet, the Rwandans had names for their different economic roles. People whose families were primarily herders and raised livestock were called “Tutsi.” People whose families were primarily farmers who raised vegetables were called: “Hutu.” These were fluid categories based on occupation and wealth. Owning cows was more expensive than farming, but if a farmer (a Hutu) had a banner year of crops and then purchased cattle, the family could become Tutsi. Approximately 15% of the population at the time was Tutsi and 85% Hutu, with less than 1% of the population belonging to the Twa—the indigenous people of Rwanda. There was intermarriage between the groups and no easy way to distinguish who was in one group or another.

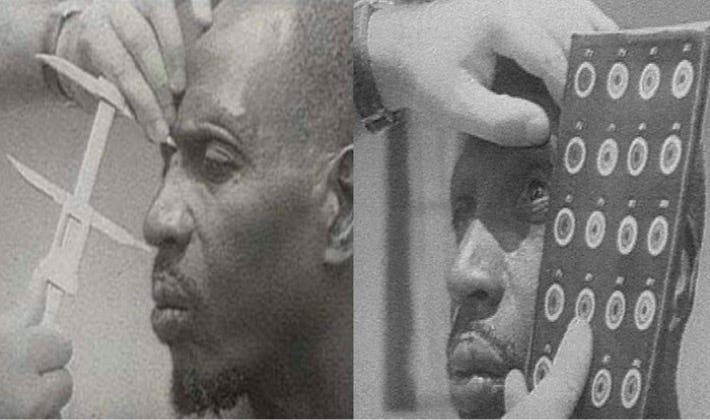

The Belgians saw an opportunity in these distinctions to practice their preferred approach to colonial administration: indirect rule. Under indirect rule, Belgium chose some people in the colony to administer their colonial “authority” on their behalf. In the Tutsi, the Belgians saw a small, higher economic class that could rule the masses. They proceeded to design educational opportunities specifically for Tutsis and others with societal privileges so that they might serve in the colonial administration. To solidify these fluid social classes, the colonizers appealed to 1930’s “race science” to sort the Rwandan population. Belgium sent scientists to Rwanda, wielding “scales and measuring tapes and calipers, and they went about weighing Rwandans, measuring Rwandan cranial capacities, and conducting comparative analyses of the relative protuberance of Rwandan noses.”2 These findings were used to classify Rwandans as either “Hutu” or “Tutsi.” The scientists found what they were looking for: the Tutsi had “nobler” and more “aristocratic” features than the “coarse” and “bestial” Hutus. As an example (see photo below), on the “nasal index…the median Tutsi nose was found to be about two and a half millimeters longer and nearly five millimeters narrower than the median Hutu nose.”3 While there may have been some physical differences that resulted from generations of herding animals (perhaps a taller or more lean build) as compared to bending over to till the red earth (perhaps shorter and stockier), these distinctions were tendencies, not genetics. The result of these examinations was that every Rwandan was issued an identity card with their name and “ethnicity” (Hutu, Tutsi, or Twa). These codified categories laid the foundation for the genocide in 1994.

The Belgian understanding of race and ethnicity was fueled by a misinterpretation of Scripture—the Hamitic Hypothesis. Based on a misreading of Genesis 9—when Noah’s anger with his youngest son (who saw his drunken nakedness and told his brothers who covered up their father) led him to curse Ham, the Father of Canaan. Noah exclaimed, “Cursed be Canaan; lowest of slaves shall he be to his brothers” (Genesis 9:25). In the process of encountering Africans, Europeans were surprised by the “advanced” civilizations in North Africa, especially in Egypt, concluding that these northern Africans must be somehow related to the superior the Nordic/Aryan “race” of Europeans. These “Hamites” (northern Africans) then were believed to be superior to the “Negroids” (southern Africans). Applying this flawed theory to Rwanda, the Tutsi were posited to have migrated to Rwanda from the north, while the Hutu migrated from the south. A clear hierarchy of Europeans>Tutsi>Hutu laid the foundation for colonial indirect rule.

After World War II, Rwanda prepared for independence as independence movements grew worldwide. As the Belgians withdrew, factions of Hutus seized power, and the first mass killings of Tutsi occurred in 1959, with many Tutsi fleeing to neighboring countries, including Uganda, Burundi, Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo), and Tanzania. The Hutu government resented how the Tutsi had ruled over them on behalf of the Belgians. There were additional mass killings against the Tutsi in 1973. In the 1980s, repeated requests from

Tutsi refugees to return to Rwanda were denied by the Hutu government, who said that Hutus were the only true Rwandans. As the Rwandans-in-exile formed a military organization, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), launching cross-border raids in the 1990s, the Hutu government attacked Tutsi within Rwanda. A peace deal was negotiated in 1993 to allow for the return of some Tutsi refugees. However, extremist Hutus opposed the agreement. After meticulous years-long planning to exterminate the Tutsi, on April 6, 1994, the Rwandan president’s plane was shot down over Kigali, and the mass killings of Tutsi began, led by the Rwandan army and official radio broadcasts. The genocide lasted one hundred days until the RPF liberated the country.

What can be learned from the Rwandan experience? In his book, Mirror to the Church, Emmanuel Katongole persuasively claims that “the crisis of Western Christianity is reflected back to the church in the broken bodies of Rwanda.”4 What happened in Rwanda in 1994 was a failure of social, political, and cultural ideologies given more power than the gospel of Jesus Christ. This was the same failure that Karl Barth and his co-authors named in The Barmen Declaration in theses 3 and 6:

3. We reject the false doctrine, as though the church were permitted to abandon the form of its message and order to its own pleasure or to changes in prevailing ideological and political convictions.

6. We reject the false doctrine, as though the church in human arrogance could place the Word and work of the Lord in the service of any arbitrarily chosen desires, purposes, and plans.

The willful blindness of the Deutsche Christen (German Christians) in 1930s Germany and the perpetrators of the Rwandan genocide is a tragic “failure of imagination,” in Katongole’s words.5 All types of tribalisms—both real and fabricated—can lead to violent outcomes, especially when the divisions are justified theologically. Social, political, and cultural ideologies cannot be given more power than the gospel of Jesus Christ. This confusion currently lies at the heart of Christian nationalism in the United States as Nazi flags were present at the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville in August 2017, and the so-called Christian flag and “Jesus Saves” posters joined the attempted insurrection at the United States Capitol on January 6, 2021.

None of us can claim that we are chosen and others are not without deadly consequences. Instead of believing in God’s selective favoritism, the gospel offers another way. In the words of Margit Ernst-Habib: “Through God’s gracious election in Christ, boundaries are broken up, definitions of who is ‘in’ and who is ‘out’ are fundamentally challenged; the ‘chosen race’ can only mean the ‘human race.’”6

For more on the role of the Church in the genocide against the Tutsi, see Marcel Uwineza, Elisée Rutagambwa, Michel Segatagara Kamanzi, eds., Reinventing Theology in Post-Genocide Rwanda (Georgetown University Press, 2023); Timothy Longman, “Church Politics and the Genocide in Rwanda,” Journal of Religion in Africa 31, no. 2 (May 2001): 163–186; and Timothy Longman, Christianity and Genocide in Rwanda (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

Philip Gourevitch, We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will be Killed With Our Families: Stories from Rwanda (London: Picador, 1999), 55.

Gourevitch, We Wish to Inform You, 56.

Emmanuel Katongole and Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove, Mirror to the Church: Resurrecting Faith after Genocide in Rwanda (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2009), 13.

Emmanuel Katongole, The Sacrifice of Africa: A Political Theology for Africa (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2011), 59–60.

Margit Ernst-Habib, “Chosen By Grace: Reconsidering the Doctrine of Predestination,” in Feminist and Womanist Essays in Reformed Dogmatics, ed. Amy Plantinga Paul and Serene Jones (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2006), 92.

Thanks for this informative piece. However, the last two paragraphs unsettled me. Whilst agreeing with your objection to 'tribalisms', I'm unwilling to give unqualified assent to Ernst-Habib's statement with which you conclude, namely: "the 'chosen race' can only mean the 'human race' ". Surely, the 'chosen race' means 'the human race' only but precisely because it first and always 'means' "Abraham and his seed forever" (cf., e.g., Gn 12.1ff; Rm 4.1ff; Rm 9-11). Unqualified, the statement suggests (to me at least) a supersessionist eclipse of Israel.

This Rwandan experience and the role of "Christian Nationalism" is unfortunate. But in what other ways is the 'church' perpetrating similar acts in Africa, especially in the name of religion? May God have mercy!