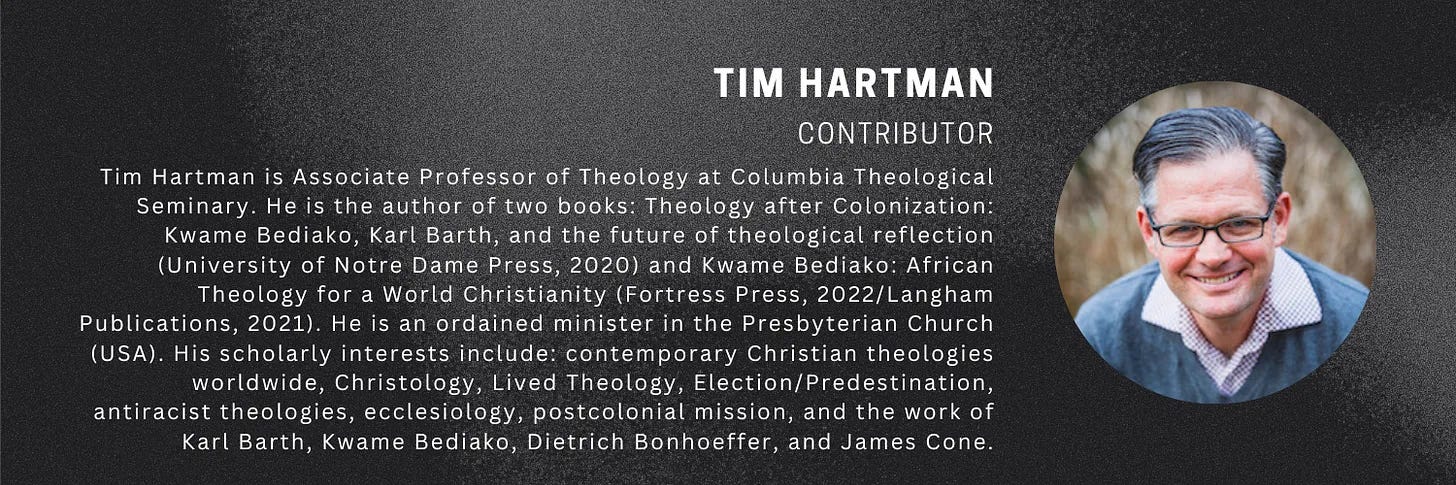

About the author: Tim Hartman is Associate Professor of Theology at Columbia Theological Seminary. He is the author of two books: Theology after Colonization: Kwame Bediako, Karl Barth, and the Future of Theological Reflection, and Kwame Bediako: African Theology for a World Christianity. He is an ordained minister in the Presbyterian Church (USA). His scholarly interests include contemporary Christian theologies worldwide, Christology, Lived Theology, Election/Predestination, antiracist theologies, ecclesiology, postcolonial mission, and the work of Karl Barth, Kwame Bediako, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, and James Cone.

All human beings have one, shared vocation: to faithfully respond with all of ourselves to the grace offered us in Jesus Christ. Human vocation is the outworking of the justification of humanity in the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ and the sanctification of humans through the work of the Holy Spirit. Cynthia Rigby writes that “‘[v]ocation’ is the way of naming how the ‘what’ of justification and sanctification is lived out in our daily lives.”1 The relationship of justification, sanctification, and vocation is not sequential, nor linear. If justification and sanctification are understood as the work of Jesus Christ, then vocation is, in Karl Barth’s words: “the co-operation of the Christian in the work of Christ.”2 As always, we must note that this cooperation is not meritorious; a Christian’s work, or effort, while significant from the perspective of the individual, merely ratifies and appropriates the work of God that has already been completed in Christ.

The work of God calling humanity to Godself began in Creation and is expressed in the covenantal formula, as expressed by God to Moses and the Israelites: “I will be your God, and you will be my people” (Ex. 6:7). As Christians live into our identities as children of God and respond to God’s initiative, we live into our vocation. In this way, we live into God’s election of Godself—to be a God for and with humanity—and God’s election of humanity—to be God’s people. God has chosen to be for us and with us. We then choose to be for God and for our fellow humans.

“Election means grace,” writes William Stacy Johnson. “It means that God is ‘for’ humanity and…that human beings should be ‘for’ one another.”3 Election is a free gift that we receive from God and that we share in common with all other humans. At times, we can forget these truths. As Barth writes,

Called to be a witness of Jesus Christ, [the Christian] finds a Lord and becomes His servant, and thus finds that he is given a definite task and definite orders. He may and will often forget or neglect these. He may and will misunderstand them and execute them in a wrong sense. But he has them. He lives with and by what is entrusted to and demanded of him.4

Our election is not for ourselves. What God said to Abram: “I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you and make your name great, so that you will be a blessing” (Gen. 12:2), is true for us as well. We are blessed to be a blessing.

Margit Ernst-Habib interprets Barth’s claim that our election comes with “a definite task and definite orders.” She writes, “the divine gift includes a task; being elected means being elected for service to God and others. …The freedom Christians can live is indeed a ‘freedom from,’ but primarily it is a joyful ‘freedom for,’ freedom for serving God and for serving fellow human beings.”5 As Christians, we have been chosen so that we may serve others. God is not instrumentalizing humanity in order for God’s work on earth to be accomplished. Rather, humanity is invited to participate in what God is already doing in the world. Christians are invited to live into the freedom that God offers in Christ. As Barth writes, “To be sure, it is not external constraint, but his own freedom, which [the Christian] owes to the grace of his Lord electing him in divine freedom, which prevents him from emancipating himself from this Lord. He is elected continually to elect this Lord and His service.”6 We are elected continually in Christ to choose the Lord and to choose service, though we may and will misunderstand and fail to live into the freedom God has for us.

Scripture is full of stories of people wrestling with their vocation, who often fail—and at times succeed—to live into the calling God has for them. This winding path is what it means to “work out your salvation with fear and trembling” (Phil. 2:12). Or, in the words of Ernst-Habib: “God’s election is only complete when it becomes actual on our side, when we make our own election to be for God in the world.”7 Johnson concurs: “God’s election to be ‘for’ humanity becomes actual on humanity’s side only to the extent that humanity, in turn, makes its own election to be ‘for’ God. To be complete, election requires not only God’s action but humanity’s action as well.”8 Election comes with a task.

We are blessed to be a blessing. We all share a common vocation with a myriad of occupations. Such communal understanding—both of election and vocation—undercuts individualistic (and nationalistic) understandings of salvation. God is only for me because God is for (all of) us. As humans, we have a shared destiny, not only on this planet, but with God. God calls us to Godself and to actively participate in God’s mission. Our goal is not personal salvation but to live into the salvation that is already accomplished by God in Jesus Christ. Our life—in response to God’s call, living for and with others—is our vocation.

Cynthia L. Rigby, “Justification, Sanctification, Vocation,” in The Oxford Handbook of Karl Barth, ed. Paul Dafydd Jones and Paul T . Nimmo (Oxford University Press, 2019), 425.

Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics IV/3 (T&T Clark, 1962), 608.

William Stacy Johnson, Mystery of God: Karl Barth and the Postmodern Foundations of Theology (Westminster John Knox Press, 1997), 63.

Barth, Church Dogmatics IV/3, 665.

Margit Ernst-Habib, “Chosen by Grace: Reconsidering the Doctrine of Predestination,” in Feminist and Womanist Essays in Reformed Dogmatics, ed. Amy Plantinga Pauw and Serene Jones (Westminster John Knox Press, 2006), 88.

Barth, Church Dogmatics IV/3, 665.

Ernst-Habib, “Chosen by Grace,” 89.

Johnson, Mystery of God, 64.

I very much appreciated this piece, Tim. Clear, succinct, and truly edifying.

My only very minor quibble is with the quotations in your 2nd to last paragraph - rendering God's election conditional on our response - emphasised in particular by both writers' use of the word 'only'.

Barth's words in the previous paragraph properly testify to the unconditional and invitational character of God's gracious election in Christ - the theme which you have so winsomely expressed in your paper.

Thank you.