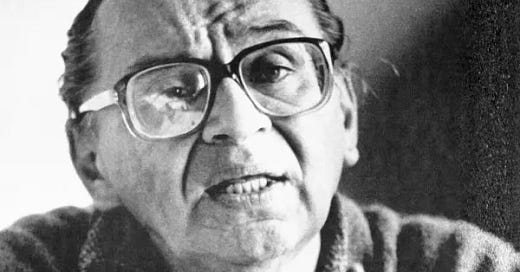

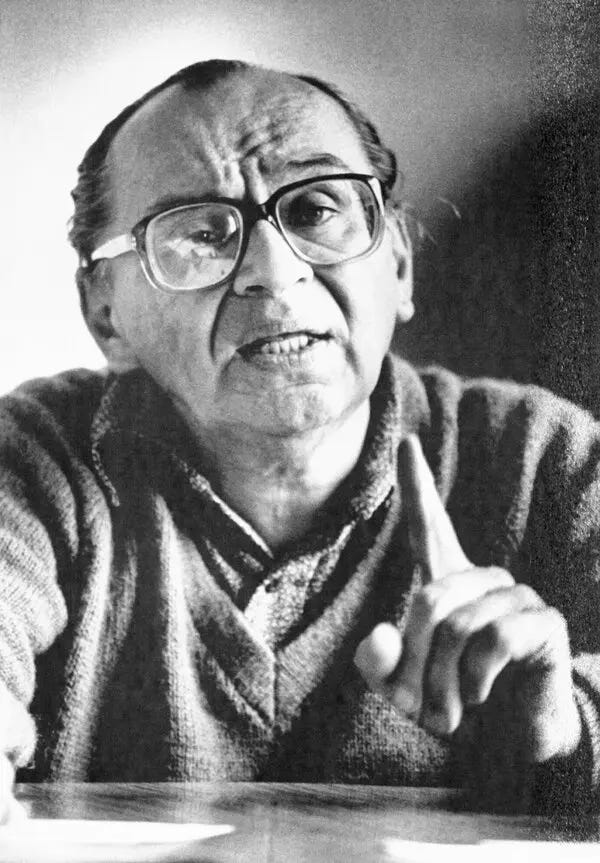

Renowned liberation theologian Gustavo Gutiérrez passed away on October 22, 2024. Professor Luis N. Rivera-Pagán wrote the following historical reflections on Gutiérrez in the broader context of theology and literature in Latin America.

About the Author: Luis N. Rivera-Pagán is the Henry Winters Luce Professor of Ecumenics and Mission Emeritus at Princeton Theological Seminary. He received his Doctorate in Philosophy (Ph.D.) at Yale University in 1970, and is the author of several books, among them: A Violent Evangelism: The Political and Religious Conquest of the Americas (1992), Mito exilio y demonios: literatura y teología en América Latina (1996), and Ensayos teológicos desde el Caribe (2013), and the editor of God, in Your Grace . . . Official Report of the Ninth Assembly of the World Council of Churches (2007).

Gustavo Gutiérrez and José María Arguedas:

The Story of a Prophetic Commission

Beginning in the sixties, two types of human spiritual creations from Latin America have grown in quality and have deserved global attention: fiction, especially novels, and liberation theology. Gabriel García Márquez, Gustavo Gutiérrez, Mario Vargas Llosa, and Leonardo Boff, to mention only some of the main authors, became widely known and read. More to the point, one discovers in both linguistic discourses surprising coincidences in social perspectives, thematic complexes, mythical allusions, and utopian expectations. Yet the analyses of the convergences and divergences, symmetries and asymmetries, between literature and theology have been few and marginal.

Let me give an example of probably the most important existential and intellectual encounter between a prominent theologian and a distinguished writer in Latin America: Gustavo Gutiérrez and José María Arguedas. Gutiérrez’s Teología de la liberación [Theology of Liberation]1 opens not with a quotation from any philosopher or social scientist but with a long citation of Todas las sangres [All the Bloods], a novel by José María Arguedas, one of the finest Peruvian writers of this century, and to whom Gutiérrez dedicates his pioneer book.

The citation has an interesting background history. In several stories, Arguedas faced, like maybe no other Latin American writer, the labyrinthine and conflictive relations between the different ethnicities, cultures, languages, and spiritual traditions in the Andes. In Agua (1935), Yawar Fiesta (1941), Los ríos profundos (1958), and Todas las sangres (1964) he dwells into the agonies and hostilities that have characterized the social interplay between the dominant white sectors, the native communities, with their diverse linguistic and cultural heritages, the Afro-Peruvian enclaves, and the baroque rainbow of mestizos and ladinos.

Reading Arguedas, one is moved by his intense love for the despised native communities, as well as by the way his style and language are seduced and beautifully reconfigured by the melody and poetry of their languages. It is a splendid transformation of pain into poetry. It is the kind of poetic pathos that one finds, for example, in Toni Morrison; the same type of intense poetic immersion in the tragedies and hopes of a suffering community. There is an awful struggle in the entrails of those beautifully construed novels: it is the epic confrontation of the different faces of Perú. There is also an obstinate utopian horizon, the dream that one day, despite the memory of violent conquest despite the legacy of centuries of exploitation, justice and peace might finally prevail. It is evidently a biblical hope, a prophetic heritage of Isaiah and Bartolomé de las Casas. The reader may also discover in Arguedas a superb reconstruction of the manifold ancient mythical traditions still resonating in the Andes, the different crossroads of the sacred and the divine, the heaviness of social sinfulness, the search for sanctity, the persistence of oneiric utopias, and the endurance of faith despite social inclemency.

In Todas las sangres, Arguedas confronts the crucial question of the meaning of God in that contradictory situation of violence and resistance, oppression, and hope. And Arguedas finds, deep in the social consciousness of his people, a clash between two opposing images of the Christian God. There is the God and the Church of the lords of the land; there is the God and the Church of the hopes of the poor. There is the God and the Church of those who have in their power the fate of the people; there is the God and the Church of those who, in the midst of their most profound misery and desperation, pray and hope against all hope. There is the God and the Church of the political powers; there is the God and the Church of the prophets. There is also the ardent and restless conscience of those who want to do right in a maze of unrighteousness. It is from such a cosmic and epic theomachy that proceeds the epigraph of Gutiérrez's famous book.

Those previous books had the majestic Andes as their social context. In his last novel—El zorro de arriba y el zorro de abajo (1969)—the social context changes to Chimbote, a coastal city. It is a strange text with two different types of discourse. On the one hand, there is the literary fiction, in which Arguedas once more strives to reconcile the warring souls of his nation, this time in a violent urban context. On the other hand, there is a writer’s diary, in which Arguedas becomes an agonizing Latin American Dostoyevsky. In the summer of 1969, Arguedas recognizes with horror that his novel goes nowhere. This means that his aspiration to bring justice and peace, to overcome centuries of tragic violence and oppression, by a literary reconstruction of reality, flounders into catastrophic failure. His writing has lost its meaning; in fact, his existence is now meaningless. The literary fiction ends in a desperate note of incoherent hope: a priest, shadowed by a crucifix and a poster of Ché Guevara, reading I Corinthians 13, Paul’s paean to agápe.

The writer’s diary has a different and highly peculiar conclusion. Arguedas proclaims that with him, a cycle in the history of his people ends, and another begins. It ends the cycle of hate, oppression, and of a God of fear. It begins the cycle of integration, solidarity, and of a God who liberates. He then engages into a sudden dialogue, expressed in a dramatic tone, with somebody whom he just calls “Gustavo”, without saying, to the chagrin of his readers, the last name of his interlocutor. That “Gustavo” was none other than Gustavo Gutiérrez, who was, at the time, a relatively unknown Peruvian priest.

Gutiérrez had visited the novelist and shared with him a conference he had recently given in Chimbote about “God the liberator.”2 On a previous occasion, Arguedas had read Gutiérrez some parts of Todas las sangres, those dealing with the different incarnations of the Christian God in Perú, the same sections that would resurface as epigraph of Gutiérrez’s Theology of Liberation. Suddenly, Arguedas, in the diary, dramatically challenges Gutiérrez, always referring to him only as “Gustavo,” to dare go and proclaim loud and clear the era of God the liberator. It is an awesome charge, a prophetic commission. It is as if the novelist, in the eclipse of his literary utopia, is able to discern that only in the God of the Exodus, of the downtrodden, of the exiled, of the resurrection of the Crucified, and of I Corinthians 13, might lie the hope to unravel what he has been unable to unknot, the dark forces of evil in the heart of Perú. Only that God, Arguedas seems to be saying, is able to exorcise the demons that haunt Perú and his own soul. In the diary, the novelist summons Gustavo to speak in his exequies; then takes out a gun from his desk and kills himself. His suicide is his last desperate aesthetic performance.

Gustavo Gutiérrez will never forget that terrible prophetic commission, proffered with the pathos and blood of the most sensitive and delicate of Perú’s novelists. He dedicated Theology of Liberation to Arguedas, prefaced it with the dramatic theomachy of Todas las sangres, and some years later wrote a beautiful essay on the novelist.3 It constitutes an exceptional example, one of the few in our history, of a meaningful dialogue between a great writer and a great theologian on the significance of God for the travails and pains, the hopes, celebrations, and dreams of a people whose destiny has been torn by misery, violence, and exploitation.4 It is the kind of meaningful dialogue that I see proposed in Mackay's The Other Spanish Christ.

It shows an utter lack of understanding of such a dialogue, the fact that the 1973 English edition of Theology of Liberation eliminated the epigraph with the citation from Arguedas, sparing its readers the pleasure and perplexity of the literary drama behind it. Only in 1988 did Orbis Books finally re-edit the book with the epigraph from Arguedas . . . in Spanish. So much for editorial sagacity! Gutiérrez’s beautiful essay on Arguedas, “Entre las calandrias,” which is maybe his best-written piece from a literary standpoint, has, so far as I know, never been translated into English.

In an address to the Peruvian Academy of the Spanish Language, Gutiérrez expresses the following reverent homage to the late novelist:

“None of us have described with such empathy and mastery the everyday pain and the inexhaustible energy of a historically neglected people . . . From an experience that weaves together anguish and hope, sorrow and joy, Arguedas goes more and more deeply into the enormous and complex reality that he wants to express and transform. At times he seems to feel that something has come back into the experience of the people with whom he has cast his lot . . . He calls it the liberating God . . . For our purposes it is enough to say that he has fully raised the question. The human density expressed in this question is an inescapable challenge to all God-talk . . .”5

And yet, Antonio Carlos de Melo Magalhães, a young Brazilian theologian, is probably right when, in a recent article, he asserts that Gutiérrez's reading of Arguedas, for all its originality and significance, does not affect substantially his theological methodology or his perspective on how to do theology. It serves as an excellent illustration of his ideas. It becomes an isolated instance, an interesting interlocution. Even if Gutiérrez alludes to Arguedas briefly in several of his writings,6 this does not lead him, according to de Melo Magalhães, into a deeper analysis of the theological import of Latin American literature, or by that matter, even into Arguedas literary corpus, as a way of discovering and reconstructing the myths, the utopias, the tragedies, and the faith of the people,7 and as a significant tool in the task of reconceiving theological discourse.

This is unfortunate, for both extraordinary Peruvians share similar feelings of solidarity, hopes of liberation, and reverence for the sacred. Both deal with similar human tragedies, with the despair of misery and violence and also with the ardent quest for redemption and liberation. Pedro Trigo, a Roman Catholic theologian teaching Latin American studies at the Catholic University of Caracas, Venezuela, has the merit of stressing in a very suggestive essay the benefits that a theologian as a theologian might derive from a critical scrutiny of Arguedas’ novels. He has also studied the religious imagery in other Latin American novelists without, however, giving much consideration to the theoretical reflection about what such an analytical enterprise might entail for theological methodology and scope.8

Towards a Dialogue Between Latin American Theology and Literature

The Cuban scholar Reinerio Arce-Valentín wrote in 1993 a doctoral dissertation for Tübingen Universität, under the direction of Jürgen Moltmann, on the religious ideas and symbols in the writings of José Martí. It has been published in German as Religion: Poesie der kommenden Welt. Theologische Implikationen im Werk José Martí.9 It opens, in my opinion, a whole new field of dialogue and discussion in the Cuban Martí studies, one that evades the dead-end of the fruitless and sterile attempts to make Martí a Caribbean Marx. It is in a sense a new Martí, or more precisely the same always-venerated Martí, but seen from a new perspective. In my opinion, it brings a hermeneutic fresh air in the Cuban dialogue at the right moment, when scholars on the island and in the diaspora are designing common spaces for intellectual collaboration that might overcome the bitter animosities of the past.10

Arce-Valentín’s book is significant also beyond the frontiers of Cuban and Martí studies. It constitutes a step forward in the dialogue between Latin American theology and literature that, according to my reading of The Other Spanish Christ, was previewed by John Mackay almost seven decades ago. If Gustavo Gutiérrez paid attention to some stories of Arguedas, Arce-Valentín unveils in the whole literary corpus of Martí an unexplored wealth of religious imagery and symbolism, which could be of inspiration for a new generation of Cuban and Latin American theologians. In so doing, he calls to our attention a statement by one of the foremost Latin American writers, Ernesto Sabato, about the crucial role of the novel in Latin American culture:11

“Not long ago, a German critic asked me why we Latin Americans have great novelists but no great philosophers. Because we are barbarians, I told him, because we were saved, fortunately, from the great rationalist schism . . . If you want our Weltanschuung, I told him, look to our novels, not to our pure thought.”12

By discounting the evident exaggeration in that statement, Sabato has a crucial point, which theologians usually ignore. The Latin American existential drama, in all its manifold complexities, has expressed itself fundamentally and in a magnificent way in our literature, especially our novels, not in philosophical treatises. To paraphrase Richard Rorty, it is in our fiction that the contingency, the irony, and the solidarity, but also the tragedies and the comedies, the sorrows and the joys, the violence and love, the desperation and hope, the myths of origin and the apocalyptic utopias, of our people find splendid artistic manifestation.

I agree with the thesis recently expounded by Vítor Westhelle and Hanna Betina Götz13 that the exploration of the myths, the utopias, and the faith immersed in our literature might be one of the ways to overcome the difficult predicament in which Latin American liberation theology finds itself, in a historical period aptly described by Elsa Tamez as one of "messianic drought" in which the horizons seem to close.14 Theirs is a robust essay that gives vent to the authors’ perplexity for the abyss prevailing between theology and literature in Latin America and, at the same time, suggests several lines of research. Antonio Carlos de Melo Magalhães in the essay cited before, published in Saô Paulo, Brazil, has deepened that suggestion and has contributed: 1) first, a brief but instructive analysis of the encounters and misencounters between theology and literature (or more generally, art) in Germany during the last two centuries, 2) second, some notes on the debate in the United States provoked by the literary biblical criticism and reconstruction of Harold Bloom and Jack Miles, 3) and third, a discussion of the ways in which three Latin American theologians have interpreted literary authors, namely, Gustavo Gutiérrez/José María Arguedas, Antonio Manzatto/Jorge Amado, and Luis Rivera-Pagán/Alejo Carpentier.

Let me say some words about the last two pairs of theologians/novelists studied by de Melo Magalhães. Antonio Manzatto has written an extended and profound theological study of Jorge Amado, possibly the most important Brazilian novelist of this century—Teologia e literatura: reflexâo teológica a partir da antropologia nos romances de Jorge Amado.15 Manzatto' study of Amado is, in my view, theologically more relevant that Gutiérrez's reading of Arguedas, for at least two reasons. First, he takes as its object of study the whole corpus of Amado, not isolated sections of some writings. Second, he does not limit his analysis to the obvious religious imagery and symbols in Amado’s novels but has a wider spectrum of questions related to the main issues of human existence in a society of so many contradictions and conflicts, as Brazil, the biggest Roman Catholic nation in the world, with several native communities trying to survive and preserve their traditions, a significant presence of African-American religiosities, and a growing number of variegated evangelical and Pentecostal congregations. Manzatto also brings to the study of Amado an impressive knowledge of Latin American liberation theology.

As in Pedro Trigo, Gustavo Gutiérrez, and Reinerio Arce-Valentín, in Manzatto, we find an effort on the part of liberation theology to reconstruct and reconceive its dialogue with Latin American culture by means of literature, but at a substantially more sophisticated analytical level. Manzatto's study of Jorge Amado is doubtless a substantial contribution to the dialogue between theology and literature. De Melo Magalhães, however, perceives what he considers a limitation in Manzatto’s perspective. Manzatto, according to de Melo Magalhães, understands the value of literary analysis for the language of theology and the identification of its social context, but not its possible transforming impact in the main theological concepts, for example, in the vision of God.

I began to explore systematically, from a theological perspective, Latin American literature in the 1996 John A. Mackay lectures, held in San José, Costa Rica. They were published that year in the journal Vida y pensamiento as “Mito religiosidad e historia en la literatura y el discurso teológico en América Latina y el Caribe” and in an expanded version in book form as Mito, exilio y demonios: literatura y teología en América Latina.16 There I faced three different themes: 1) Afro-Caribbean religiosity and cultural traditions in several novels of the Cuban Alejo Carpentier; 2) The idea of exile and the heterodox religious imagery in the poetry of León Felipe, a Spanish émigré living and writing for more than three decades in México; 3) Demonology and exorcism in Gabriel García Márquez’ exciting novel Del amor y otros demonios [Of Love and Other Demons] as a symbol of the eighteenth-century profound crisis of Spain’s spiritual hegemony over its Latin American colonial possessions. The introduction of the book elaborates all too briefly on some theoretical considerations and suggests other themes suitable to theological reflection in the works of several Latin American writers. As is the case with Gustavo Gutiérrez, Reinerio Arce-Valentín, Pedro Trigo Antonio Manzotto, and Antonio Carlos de Melo Magalhães, my own conceptual perspective is deeply imprinted by liberation theology, whose demise has so many times been prematurely announced.

The always critical and brilliant de Melo Magalhães considers Mito, exilio y demonios "a significant step forward” in the dialogue between theology and literature in Latin America, for it brings to the fore not only a theological appreciation of the main authors and writings, but also an inquiry into the implications of that dialogue to the language, contents, and concepts of theology, positing thus, according to de Melo Magalhâes, “an alternative to the normative theological enterprise.” However, adds de Melo Magalhâes, “Rivera Pagán . . . does not develop a reflection that might problematize the consequence of the need to redesign the theological methodology. He indicates the goal but does not clarify the roads to get there.” Touché! His final sentence is, fortunately, less severe: “[Rivera Pagan’s] interpretations of the authors are fascinating and possess great theological wealth.” Oh well, thanks!

My proposal to revive and renew Mackay’s project of a dialogue between Latin American theology and literature obviously does not refer to the reading of fiction and poetry for distraction (diversion, would Pascal say with acrimony), for pleasure, or to improve our writing skills, as legitimate as these purposes be. It is rather a crucial intellectual enterprise to understand, in a particular social context and a specific cultural tradition, the concrete historical shape of the perennial agony between love and death, éros and thánatos, agony understood here as agônía, in the Greek sense of the term as emphasized by Miguel de Unamuno in The Agony of Christianity, a book much admired by Mackay. Mikhail Bakhtin has eloquently described that agônía, as a key dimension of art:

“Only love is capable of being aesthetically productive; only in connection with the loved is fullness of the manifold possible . . . All abstract formal moments become concrete moments in the architectonic only when they are correlated with the concrete value of the mortal human being . . . All temporal relations . . . reflect the life and intentness of the mortal human being . . .”17

The pathways of love and death, of solidarity and violence, in their manifold social and historical manifestations, and in their utopian horizon, that Émmanuel Lévinas has so aptly named “utopie de la conscience” abounding, in his view, in Latin America,18 is nowhere better expressed than in the imaginary recreation of reality that is our literature. It is also, as an act of demiurgic hubris, a way of approaching God. Literature is thus an essential partner of dialogue for theology.

The possible interlocutors in that dialogue are many: Carlos Fuentes, Alejo Carpentier, Edgardo Rodríguez Juliá, Gabriel García Márquez, Juan Rulfo, Mario Benedetti, Jorge Luis Borges, Cristina Peri Rossi, Senel Paz, Isabel Allende, Eduardo Galeano and Gloria Anzaldúa. Let me now suggest just one: Jorge Luis Borges. For several reasons, Borges is a master of the short story, one of the best in world history, at a par with Poe, Maupassant, or Kafka. The English readers now have the opportunity to enter into the enigmatic and mysterious literary labyrinths deceitfully yet genuinely true, crafted by Borges. In 1999, Penguin Books edited three excellent volumes of Borges's writings to commemorate the centennial of his birth—Collected Fictions, Selected Non-Fictions, and Selected Poems.

But, more to the point, Borges is a mine of theological provocations waiting to be explored. His story “Three Versions of Judas” is one of the most suggestively heterodox treatments I have ever read about the Incarnation and kenósis. “The Immortal” brings masterfully to the fore the issues of time and eternity, and mortality and immortality. “The Theologians” should be a required text for all those who wonder in the subtleties of the debates about orthodoxy and heterodoxy in the history of doctrines. “Averroes’ Search” could be an excellent point of departure for reflecting on translation and hermeneutics. “The Gospel According to Mark” could be read as a modern Latin American parable about the crucifixion of Christ and the idea of atonement. “Everything and Nothing” is a magnificent short riddle about identity and the self, of both humankind and God. He also has a delightful story—"The Book of Sand"—about a Scotsman Presbyterian seller of Bibles, which begins with an exchange about different Bible versions (Wyclif's, Valera's, Luther's) and ends deep into the enigma of how could God's infinite knowledge be encompassed in a finite human book.

All these theological and cultural expressions were often used and converged by the great and never-forgotten theologian Gustavo Gutiérrez.

The first edition of Teología de la liberación is from 1971, by the Centro de Estudios y Publicaciones, Lima, Perú, reprinted in 1972 by Ediciones Sígueme, in Madrid, Spain. Orbis Books published it in English in 1973. In 1988, a revised edition came from the same publishing house. It has become the classic work of Latin American liberation theology.

Arguedas refers to a conference given by Gustavo Gutiérrez on July 1968, at Chimbote, Perú. It was published as “Hacia una teología de la liberación (Montevideo, 1969), and in English as “Notes on a theology of liberation,” In Search of a Theology of Development (A Sodepax Report, 1970). It is reproduced in Alfred Hennelly, ed., Liberation Theology: A Documentary History (Orbis Books, 1990), 62–76.

“Entre las calandrias: un ensayo sobre José María Arguedas.” Instituto Bartolomé de las Casas, 1990. This essay had appeared also in slightly shorter versions in Pedro Trigo & Gustavo Gutiérrez, Arguedas, mito, historia y religión (Lima: Centro de Estudios y Publicaciones, 1982), 241–277, in Pablo Richard, ed., Raíces de la teología latinoamericana (DEI/CEHILA, 1987), 345–363, and in the journal Páginas (Lima), no. 100, December 1989.

On the subject of the relation between Gutiérrez – Arguedas, the best available analysis is from Brett Greider, Crossing Deep Rivers: The Liberation Theology of Gustavo Gutiérrez in the Light of the Narrative Poetics of José María Arguedas. Ph.D. doctoral dissertation, Graduate Theological Union, 1988. See also Curt Cadorette, From the Heart of the People: The Theology of Gustavo Gutiérrez (Meyer Stone Books, 1988), 67–75.

Gustavo Gutiérrez, “Theological Language: Fullness of Silence,” in The Density of the Present: Selected Writings (Orbis Books, 1999), 186–207.

The Power of the Poor in History: Selected Writings (Orbis Books, 1983), 19, 21, 204; We Drink From Our Wells: The Spiritual Journey of a People (Orbis Books, 1984), 21, 139, 152; On Job: God-Talk and the Suffering of the Innocent (Orbis Books, 1987), xi, xv–xvii, 105, 106.

"Notas introdutórias sobre teologia e literature," Cadernos de Pós-Graduaçâo (Instituto de Ensino Superior, Sâo Paulo) no. 9, 1997, 7–40.

Pedro Trigo, Arguedas, mito, historia y religión (Centro de Estudios y Publicaciones, 1982); Cristianismo e historia en la novela mexicana contemporánea (Centro de Estudios y Publicaciones, 1987); "Teología narrativa en la nueva novela latinoamericana," in Richard, Raíces de la teología latinoamericana, 263–343.

Religion: Poesie der kommenden Welt. Theologische Implikationen im Werk José Martí, Band 10 (Concordia Reihe Monographien, 1993). This dissertation has been published in Spanish as an abridged version: Religión: Poesía del mundo venidero. Las implicaciones teológicas en la obra de José Martí (Consejo Latinoamericano de Iglesias, 1996).

On this subject, see the important book edited by Raúl Fornet-Betancourt, Filosofía, teología, literatura: aportes cubanos en los últimos 50 años, Band 25 (Concordia Reihe Monographien, 1999).

Religion: Poesie der kommenden Welt, 30.

Ernesto Sabato, The Angel of Darkness, trans. Andrew Hurley (Ballantine Books, 1991, orig. 1974), 194.

"In Quest of a Myth: Latin American Literature and Theology," Journal of Hispanic/Latino Theology 3, no. 1 (August 1995): 5–22.

"Cuando los horizontes se cierran: Una reflexión sobre la razón utópica de Qohélet," Cristianismo y sociedad 33, no. 123 (1995): 7. See also Elsa Tamez, When the Horizons Close: Rereading Ecclesiastes (Orbis Books, 2000).

Sâo Paulo: Ediçoes Loyola, 1994.

“Mito religiosidad e historia en la literatura y el discurso teológico en América Latina y el Caribe,” Vida y pensamiento (Seminario Bíblico Latinoamericano) 16, no. 1 (1996): 5–115; Mito exilio y demonios: literatura y teología en América Latina (Publicaciones Puertorriqueñas, 1996).

Mikhail Bakhtin, Toward a Philosophy of the Act (University of Texas Press, 1993), 64–5.

Émmanuel Lévinas, De Dieu que vient à l’idée (Librairie Philosophique J. Vrin, 1982), 132.