Barth, Karl. Deliverance to the Captives. Translated by E.H. Goddard and T.H.L. Parker. Wipf & Stock, 2010. Originally published in 1961.

Every generation faces the question: Where is God for those behind bars? In Deliverance to the Captives, Karl Barth offers a potent answer—not from the safety of an ivory tower but from the pulpit of a Swiss prison chapel. These short, electrifying sermons are not watered-down abstractions. They are theology in the flesh, spoken to those stripped of power, status, and sometimes hope.

Barth's voice in this volume is not the thundering dogmatician of Church Dogmatics. Instead, it is the tender but firm voice of a preacher, one who dares to proclaim the nevertheless of the gospel to those society would rather forget.

“Nevertheless I am continually with thee; thou dost hold my right hand.” (Psalm 73:23)

This line, from one of the earliest sermons in the collection, encapsulates Barth’s theology of divine accompaniment. In a context saturated with guilt, abandonment, and the psychological weight of incarceration, Barth offers not pity but solidarity. God does not hover above the suffering. In Jesus Christ, God takes the place of the prisoner.

A Gospel for the Incarcerated

One of the most moving features of Barth’s prison sermons is his refusal to sanitize the human condition. He speaks directly to the weight of sin, shame, and despair. And yet, he does so not with condemnation, but with hope grounded in divine initiative.

“By grace you have been saved!” (Ephesians 2:5)

“This can only be said by God to each one of us... No man can say this to himself.” (p. 36)

Barth offers no false promises of quick release or moral rehabilitation. Instead, he insists that the gospel is not earned, not achieved, but rather, the gospel is given. Grace arrives like water to the thirsty and light to those trapped in darkness. And in prison, that darkness is not a metaphor. It is the air they breathe.

Christmas, Easter, and the Cross Behind Bars

Even Barth’s seasonal sermons refuse sentimentality. At Christmas, Barth reminds his hearers that “unto you is born this day a Savior”—you, the prisoner, the forgotten, the guilty (p. 23). On Easter, he declares that Jesus’ resurrection means not only his life, but “you will live also” (p. 29). And in every sermon, the cross looms large—not as a symbol of judgment, but as the act of God’s descent into the worst of human suffering.

The incarcerated are not passive recipients of grace in these messages. They are invited participants in a divine story of restoration and hope. Even as Barth names the real weight of sin, he repeatedly insists that “the door of our prison is open” (p. 40)—a spiritual, even cosmic liberation, whether or not the bars are ever physically removed.

Why These Sermons Matter Now

At a time when incarceration continues to function as a tool of social abandonment—disproportionately impacting the poor, the mentally ill, and communities of color—Barth’s sermons are startling in their relevance. He refuses to speak about prisoners; he speaks to them. And in so doing, he testifies to a God who does not distance but draws near, who does not discard but redeems.

“The real prison is in the heart of each one of us, and the gospel offers deliverance to all of us captives.” (Preface, p. 10)

Barth’s Deliverance to the Captives reminds us that theology is not a luxury for the free. It is the lifeline for those in chains. And it bears witness to a Christ who, in being for us, refuses to be anything less than the God of the imprisoned.

An Invitation: The 2025 Karl Barth Conference

This year’s Karl Barth Conference at Princeton Theological Seminary, titled “The Incarcerated God: Thinking with and beyond Barth on the Prison System,” will extend this conversation. How might Barth’s theology offer tools for resisting carceral logics? What might it mean to embody a theology of solidarity in spaces of captivity?

Learn more and register here:

ptsem.edu/academics/centers/center-for-barth-studies/2025-barth-center-conference

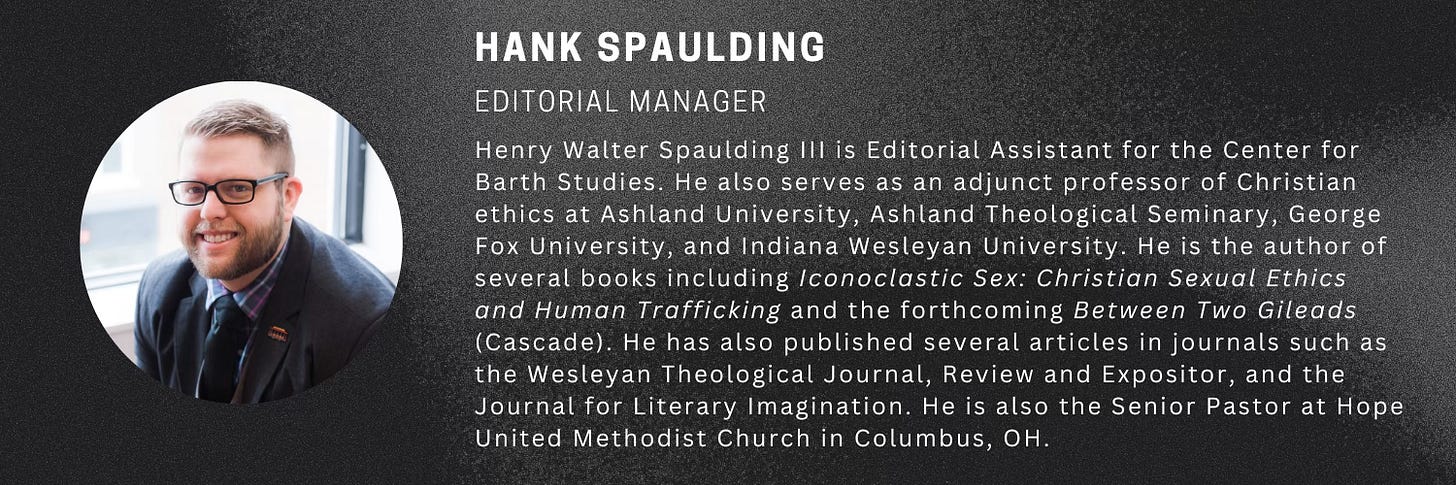

Thank you, Pastor Spaulding for calling your readership to the attention of this slim volume of Barth's sermons from 1954 to 1959, preached primarily at the Basel prison. I have returned to them often over the years, because they are Barth at his best. Barth's theology informs each sermon, but they are not didactic, they are empathic and still fresh, and without condescension. Here readers may hear Barth as a messenger of hope for every prisoner and for us all.

James Kay